In a country as overbuilt as India, we need to rethink architecture and design as a social science that emerges from local situations

In a country as overbuilt as India, we need to rethink architecture and design as a social science that emerges from local situations

A recent seminar in one of Mumbai’s fancy hotels was titled ‘Transformative Design – the Future of Architecture’. Including speakers from India, Dubai and Singapore, its glowing internationalism upheld ideals of conservation, materiality, spatial confluence, green envelopes, curtain walling systems, shade and environmental protection, energy harnessing, waste management, electrical grid and distribution systems, design for the differently-abled, façade and elevation treatments, and building face lifts. So comprehensive was the scope of the conference, it left nothing to chance.

The large audience of designers, students and practising architects filed in dutifully behind meeting room banners that proclaimed in bold type, ‘Urban Transformations in Regional Contexts’, ‘Biospheric Conservation’ and ‘Ecological Constructs’. However muddled and mismatched the titles of the various presentations, all day in meeting rooms and conference halls, a steady drone was heard with slide displays of new shopping centres, nursery schools, office buildings, and spas in the hills — the celebration of a profession that had created its own false language.

Design, of which architecture is merely a small part, is today testing the impatience of the designer and attempting to set new standards of irrelevance. Application of aesthetics is no longer just a convenient foothold in architecture, but appears everywhere and every day in whatever we do; design is like a hungry termite let loose in an old wooden warehouse. A perfectly good professional dentist for many years, my neighbour chose to abandon fixing teeth to creating fake smiles — a specialised advancement of which she was particularly proud. Her house was recently refurbished with a mirrored glass façade announcing a clinic for aesthetic dentistry. The BMWs that pulled in regularly made clear the high demand for it.

Ideas of change

Without much effort design began to cross the threshold into irrelevance in the 90s, the moneyed era of globalisation. Today, it has crossed further from genuine uselessness into utter redundancy. Even architecture is being marketed and sold as a large urban product with new consumer features and finishes: glass wall, curved wall, leaning wall, cantilevered wall, wall masked in hand tile, wall with brick veneer or steel panels, perforated with louvres, covered in traditional jalis, reshaped in movable grilles, framed or frameless, shaded or exposed. Building smart, building stupid, building on site, building pre-cast, building on demand, building without will, without constraint. The choices are so many, they escape across rooftops, down the street, never to be noticed.

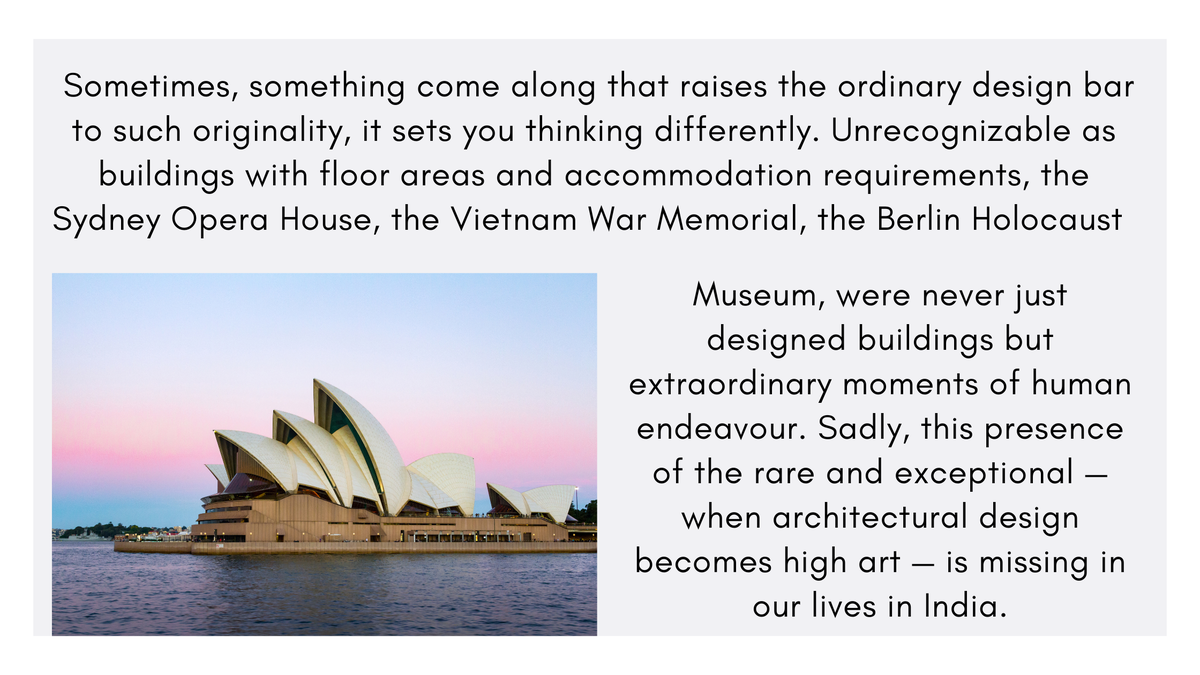

Why then is today’s architecture and design mired in such demoralising anonymity? Given the great mass of creative talent available in the country and rising number of reputable design schools, what would it take to rethink architecture as a social science that emerges from local situations, rather than an isolated object of art?

Could parked public buses be used for housing the homeless at night?

A couple of years ago, Rajesh Advani, a young architect, reacting precisely to such a call, advanced an elaborate initiative called Unbuilt India — an active search for a collective of architectural ideas that could change the country. An overwhelming response from students and professionals gathered a vast array of designs: from constructing high-rise parks in dense neighbourhoods, covering roads with vegetable gardens, reviving water sources in drought-hit areas, inserting housing for the homeless under flyovers, pedestrianising polluted urban centres, designs for tree houses, and stacked tunnel houses saving city land, among others. Drawings came off architectural shelves and out of office computers in so varied a range, it was enough to give a complete makeover to India’s thoughtless and desperate cities. The initiative was so heroic in scope and rife with such possibility, it was only natural for it to be rejected in a country consumed by self-doubt and lacking public confidence.

A proposal for a tree house

Wheat fields on buildings

So far the Indian approach has been wholly adaptive. The electric car appeared in California a decade ago, it is visible now on Indian roads. In the 1950s, American kitchens began using the electric mixer; in the 1960s Indian kitchens were fitted with the Sumeet mixie. Cities like Bogotá and Jakarta created BRT systems for their roads; a decade later, the system was tried in Delhi and Ahmedabad. The modern steel cable bridge was built in New York in 1900; the Bandra Worli Sea Link appeared a century later. Indian willingness to take design leaps meekly follows well-tested ideas in other places. In fact, the history of design has just been a history of borrowing.

For our cities to change direction, four things need to happen.

First, there is a need to move away from a piece-meal city to one that consolidates all scales of life into a flexible working model — to make domesticity, work-life, recreation, energy and transport interdependent in such a way that it relieves municipal authorities of coordination. Some small successful initiatives are already visible in India, like the public cycle track system in Pune, the clean water drive in Udaipur, waste management in Surat, and greening of streets in Bhubaneswar.

Sensor-fitted garbage bins in Surat alerts officials when it is 70% full thereby avoiding garbage overflow

Ultimately of course, urban climate action will demand a more cohesive approach that sets all these ideas into motion in a single place. It is not entirely outrageous to imagine a future where a car plugs into a house when not in use, and the house plugs into the city grid, while the city itself is part of a countrywide urban map.

Second, the use of extreme technologies and radical approaches. Could architecture be lifted up in the air to free up precious land? Could wheat fields appear on the sides of buildings, the way vegetable gardens germinate in Singapore? Could India’s polluted rivers be a source of new types of aquatic plant food? An American clothing designer recently fabricated an overcoat for the homeless of San Francisco, which converts into a sleeping bag at night. Could parked public buses be used for housing the homeless in Delhi at night? Growing inequity calls not for more regulation or urban bye-laws, but a moral response — a form of civic self-regulation that engenders both community and privacy, and allows everyone a real affordable stake in the city.

Perhaps, rice paddies at Select City Walk?

The third, an enlargement of this idea, would call for a radical revision of city bye-laws that allows a more flexible use of public and private space. The city can then offer selfless acts of generosity and gifts of the spirit to citizens: surprise gardens hidden behind walls, places of seasonal variations, monsoon greens or summer fountains.

Finally, given the country’s population density and available land mass, India is grossly overbuilt. If there is a future scenario for design, it will mostly step away from merely trying to fulfil the required statistics on roads, housing, utilities, industries and infrastructure, and instead consider what to build, what to adapt and change, and what to un-build.

Could the abandoned nuclear power plant at Dadri, outside Delhi, be converted into a museum like the Tate Modern?

A Parliament out of a 3D printer?

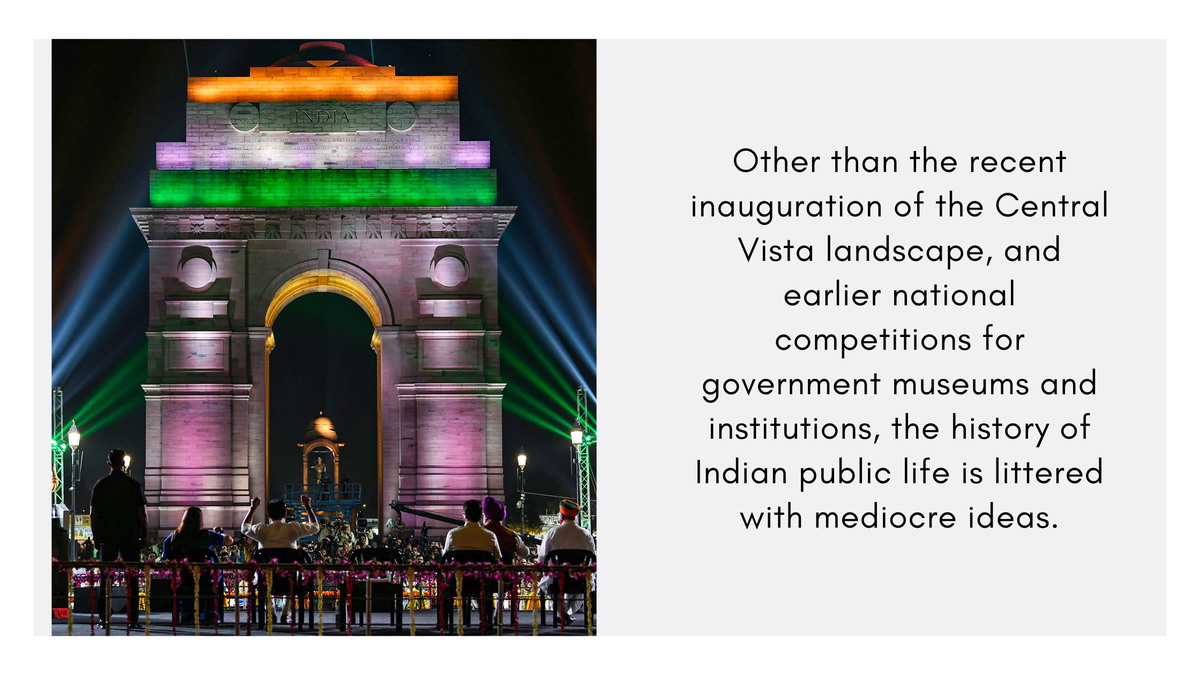

More and more, the radical view must ask awkward and impossible questions. Could the abandoned nuclear power plant at Dadri, outside Delhi, be converted into a museum like the Tate Modern, or an unusual theatre complex? Would the government consider using the entire stretch of the Central Vista to recreate underground galleries and museums? In fact, could the new Parliament and other buildings appear out of a 3D printer, without years of construction dust and air pollution?

The search for unusual, hybrid and tangential ideas must learn to deploy the stupid, the irrational, and the subversive to arrive at surprising solutions. Sometimes these may prove successful; sometimes, they may be senseless failures.

One of the many drawbacks of current architectural practice is the absence of constructed subversion — an idea that pins the hope on a future filled with new possibility. It is what a magician describes as ‘conjuring a creative imbalance’, working on the edge of getting your secret discovered, the hope that an audience pins on the failure of an impossible act. When it fails, it is serious tragedy — and comedy. When it succeeds, it crosses an unknown frontier.

The writer is an architect and sculptor, and the author of Blueprint.