Tribal and traditional artists explore novel ways of storytelling, experimenting with colour, techniques and contemporary themes, to connect with younger, mainstream audiences

Tribal and traditional artists explore novel ways of storytelling, experimenting with colour, techniques and contemporary themes, to connect with younger, mainstream audiences

The unusually sultry September and a busy makeshift stall, do not stop Rupsona. A folk singer-artist of the pattachitra tradition, from Pingla district, West Bengal, she narrates her scrolls through song, armed with a powerful voice. Undeterred by visitors trying to catch her art on camera, she points to her canvas and sings of the playful love Radha and Krishna share. Lately, her canvases have been telling some socially relevant stories as well: of female infanctide, the tsunami of 2004, and even the life of Mother Teresa.

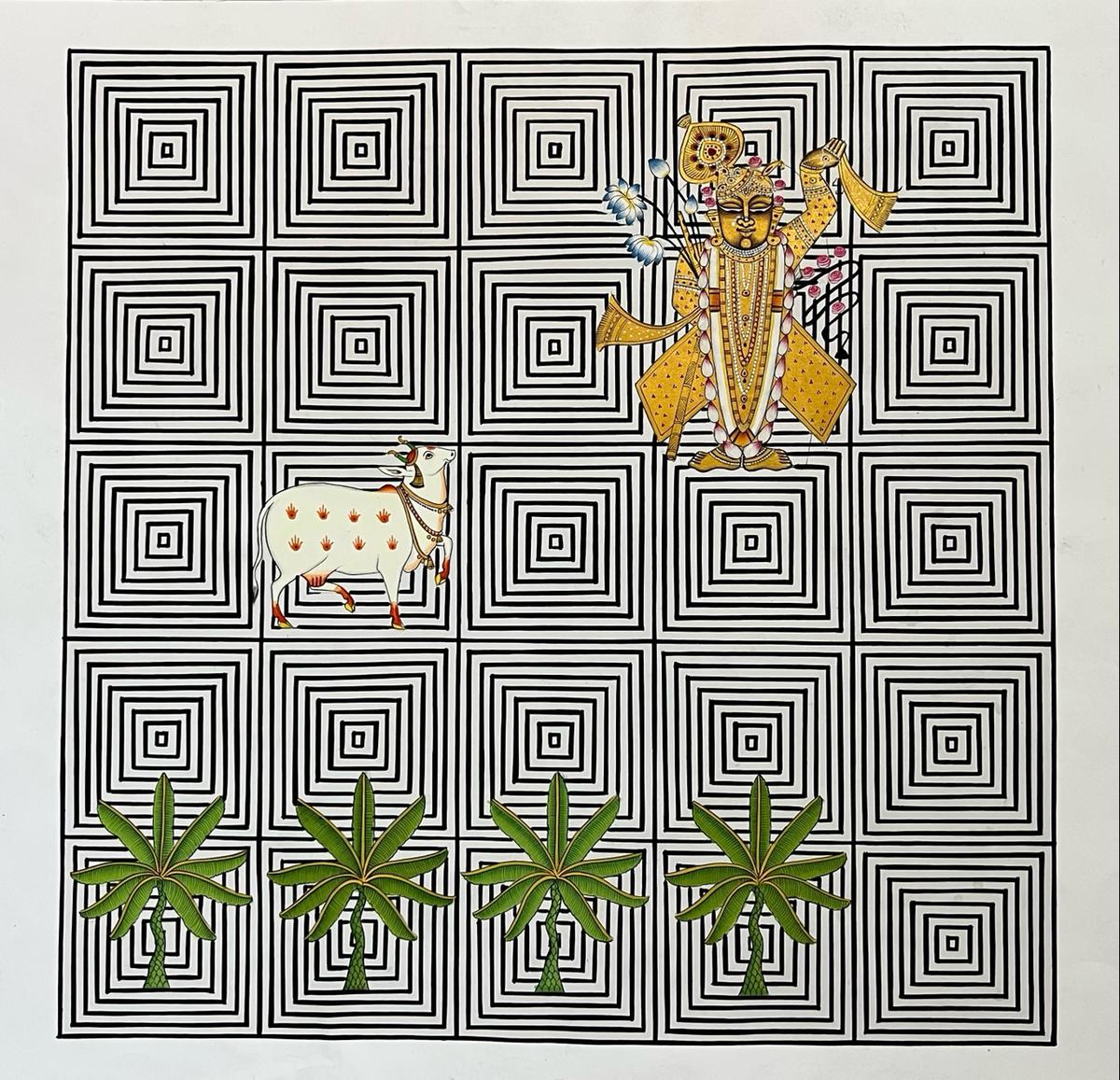

At another stall in Craft Council’s recently-concluded Artisans Collective in Chennai, a pichwai cow adorned with ceremonial jewelry dominates a stretched canvas, to the backdrop of an unexpectedly trendy monochrome grid. The Warli artist opposite holds out canvases where traditional tarpa dance and geometrical figures have now been replaced by the Tree of Life, painted in acrylic. Nearby, Bhil artists display the Hindi alphabet drawn in their traditional style to introduce children to the tribal artform.

A warli painting showcasing the Tree of Life

| Photo Credit: SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Traditional Indian artforms, a treasure trove rooted in the deepest trenches of culture, are thus adapting to the changing sensibilities of domestic and international art buyers: through contemporary themes, social messaging and experimental mediums. The reasons are many: wider reach and visibility, changing demands of the varying clientele, and the artists’ personal desire to upskill and rise as a brand. “All this, without compromising the ethos of the art,” reminds Mala Dhawan of A Hundred Hands, a Bengaluru-based organisation that bridges the gap between clients and artisans.

While characters from Hindu mythology and Nature remain primary subjects of centuries-old traditional and tribal arts , conscious innovation by third, fourth and fifth generation artists is introducing novel ways of storytelling.

Now, pichwai cows or kamdhenus — trusted companions of Radha and Shrinathji, usually a silent witness to all his leelas – can be protagonists too. Naveen Soni, a third generation pichwai artist from Nathdhwara, Rajasthan, shows the cow as an all-encompassing character: a scene unfolds inside its ornate body, as Krishna and Radha reappear. It is abstract to an extent, and will easily fit into a home with contemporary decor.

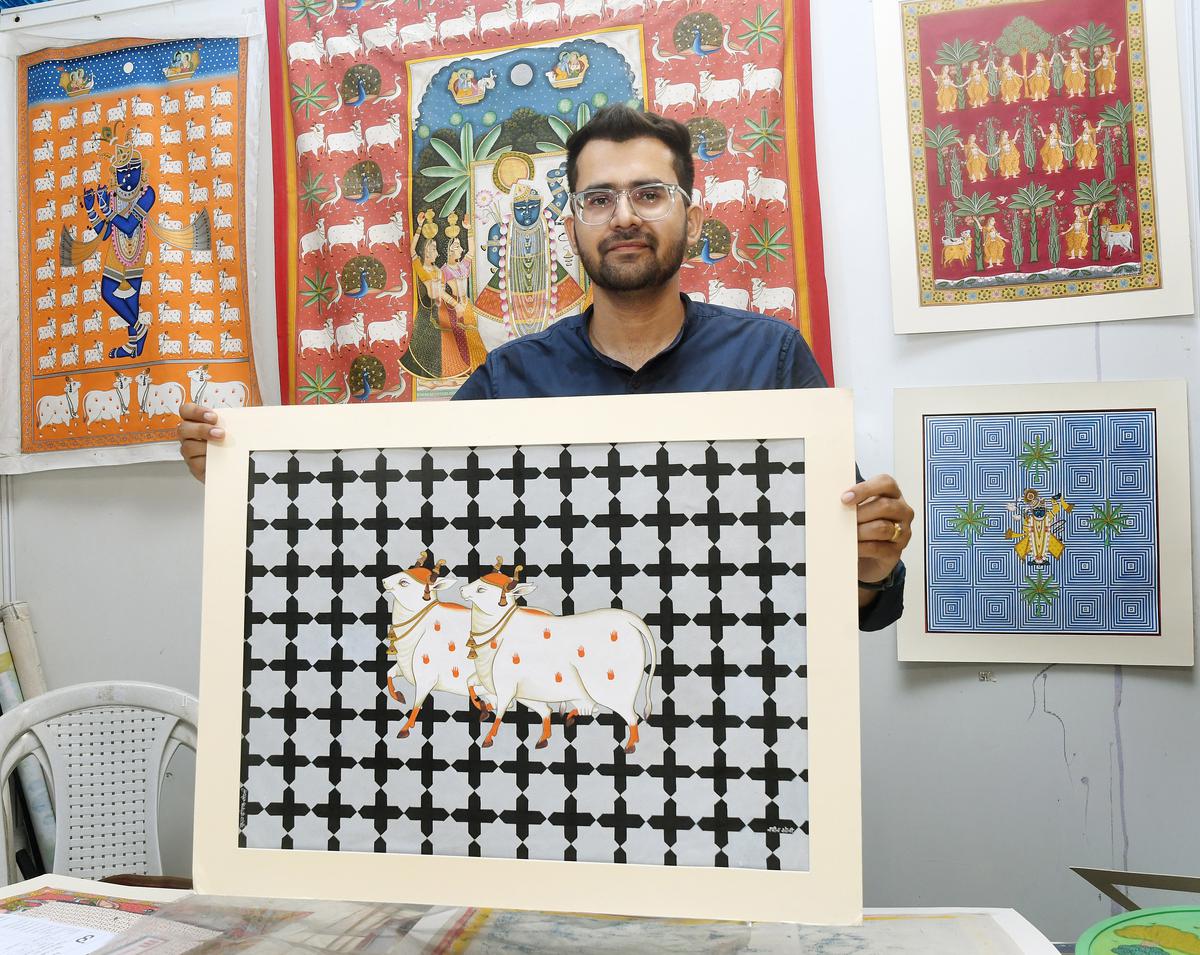

Pichwai artist Naveen Soni with his ‘optical illusion‘ work

| Photo Credit: RAVINDRAN R

“We have amalgamated some modern subjects in these pichwais, while sticking to the traditional style of drawing,” says Naveen. Modernising, according to Naveen, also means the marriage of elements from different schools of the same traditional artform that emerged in the 17th Century, revolving around the central character of Shrinathji. Pointing to a canvas, he explains, “Here, you can see trees from different schools of Indian miniature painting like Kishangarh school and Pahadi school in a single painting.” Traditionally, a pichwai that is inspired from flora-fauna themes are unheard of, but Naveen has innovated with birds, trees and some animals – other than kamdhenu – to keep up with the changing demands of his clientele.

It has only been four months since he introduced his ‘optical illusion works’ in the market. “ In exhibitions, most of the optical illusion works get sold on the first day itself!” And most are bought for office buildings and work spaces, more than homes. “It is time consuming, and is a different skill.”

“As much as we would like to modernise, it is important to keep the essence of the artforms intact,” says Gond artist Bhajju Shyam, from Patangarh, Madhya Pradesh, home to the indigenous Gond Pradhan tribe. There is no bigger authority who can opine on the evolution of traditional art than Bhajju: over the last decade he has reimagined Gond art, which relies heavily on animal forms, in imaginative ways from murals in Delhi and Singapore to hardbound children’s books, such as The London Jungle Book by Tara Books where The Big Ben is a Gond hen. Nature-led symbols, themes and legends remain the same in his works.

Rupsona, a pattachitra artist, with her scrolls

| Photo Credit: RAVINDRAN R

The Padma Shri awardee’s sole purpose is to popularise the artform so it enters mainstream galleries. Speaking from Delhi, where he is showing alongside contemporary artist Manjunath Kamath, Bhajju says, “It is such kinds of collaborations that push us to think in a contemporary way.” In Singapore’s Little India, Bhajju’s collaboration with Singaporean contemporary artist Sam Lo resulted in a facade (Broadway Hotel) that celebrates Nature.

Translating a form that is rooted in tradition on walls required a lot of learning, says Bhajju: it took him a while to get used to the idea of stencils and spray paint. But he sees this change as a gateway to mainstream audiences. “It acts as a form of preserving the gods we worship, and our Adivasi stories and practices,” says Bhajju.

Gond artist Bhajju Shyam experimenting with a stencil

| Photo Credit: special arrangement

The market and its many moods

Adapting to today’s market did not happen overnight. “For instance,” says Mala, “this year, we took five symbols which were Nature-led, and created a mood board that looks at patterns and colours, more than the motifs. Most of our traditional artforms don’t have a design background. In this way, an artisan is forced to think differently.” Consumer insights play a crucial role in understanding what to glean from the artform. “People come into the bazaars asking, ‘what is new?’” The new customers don’t want to see the same elephant being churned out, for every work. They are also looking for exclusivity, and they see value in it,” says Mala. “It is also mentally stimulating for the artists.”

Pichwai motifs and elements set against a monochrome, ‘optical illusion’ grid

| Photo Credit: special arrangement

Today’s artist has moved from re-creating to manifesting personal thoughts and idioms, says curator Tulika Kedia, whose Delhi-based Must Art Gallery has been working closely with traditional arts such as Madhubani, warli, Kalighat, Phad, Gond, Kerala murals and pattachitra, for the past two decades. “Now, we see social discourse, political flux, scenes of contemporary life, fantasy, adversity, all depicted in the art,” says Tulika.

Bhajju dates this pivot, albeit slow, to the last decade. He says, ”People have been wanting our art in their homes and private collections, which is encouraging.” And they are willing to spend. “While at an exhibition in Delhi before the pandemic,” says Naveen, “many people said that they didn’t want to purchase works with ‘cows’. Many were also not interested in religious scenes. That’s when we realised that if we have to remain in the market, we have to bring new subjects that can be put up anywhere.”

More recently, there has also been a heartening movement among young art connoisseurs in their 20s and 30s, who make up a sizable part of their clientele. Tulika says, “There is a bona fide understanding and respect for folk art. They visit galleries, go for heritage walks, participate in workshops, and are even investing.”

Miniature art, known for its painstaking detailing

| Photo Credit: SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

The young buyers, like the IT-entrepreneur crowd, are definitely interested investing in traditional art, says Mala. “We have seen Gond artists who were selling art for say ₹5000, 10 years ago, now selling for about ₹1 to 1.5 lakhs. That only comes with appreciation,” adds Mala.

Having said that, the pandemic has forced the art market and artisans to price themselves competitively. “People have become a bit more conscious. If one is spending ₹20,000 or ₹30,000 for a piece of art, they won’t think twice about moving up to ₹35,000 or 50,000. But if I am looking for a piece of art for ₹600 to 800, I probably won’t cross ₹1500 also. There is a big market for the latter,” says Mala. Innovative and modernised art also fall in the latter category, since their clientele is younger.

As they pivot towards the mainstream, younger traditional artists are hopeful about this shift. After all, it is what keeps the art relevant through the times. But they are also aware of the sanctity of the artform, and is unwilling to compromise when it comes to skill and effort. Concludes Navin, “It is important to be relatable. At the end of it all, art is all about that, isn’t it?”