This trend, in a way, shows the impact of two years of hybrid or work-from-home-based office culture that has permeated all organisations. During this time, a growing number of Gen Z and millennials have grown tired of not being recognised or compensated for putting in extra hours. Now, they want to end the burnout, and are looking to focus on work-life balance. Their online movement centres around self-preservation and doing what they are paid to do.

This trend, in a way, shows the impact of two years of hybrid or work-from-home-based office culture that has permeated all organisations. During this time, a growing number of Gen Z and millennials have grown tired of not being recognised or compensated for putting in extra hours. Now, they want to end the burnout, and are looking to focus on work-life balance. Their online movement centres around self-preservation and doing what they are paid to do.

Social media is now the public square, and quirky two words prefixed with a hashtag can make a difference almost instantly. Some go viral and stay longer than others. At times, they raise an important yet overlooked aspect of today’s work practices.

The recent two words trending on social media, more so on TikTok, is “Quiet quitting”. The phrase has generated millions of views on the short-video streaming platform. Those promoting the idea appear to be young workers who have rejected the idea of going the extra mile at work. This group seeks to make people take time out of work and do something outside of office.

This trend, in a way, shows the impact of hybrid or work from home-based office work culture that has permeated all organisations in the last two years. During this time, a growing number of Gen Z and millennials have grown tired of not being recognised or compensated for putting in extra hours. Now, they want to end the burnout, and are looking to focus on work-life balance. Their online movement centres around self-preservation and doing what they are paid to do.

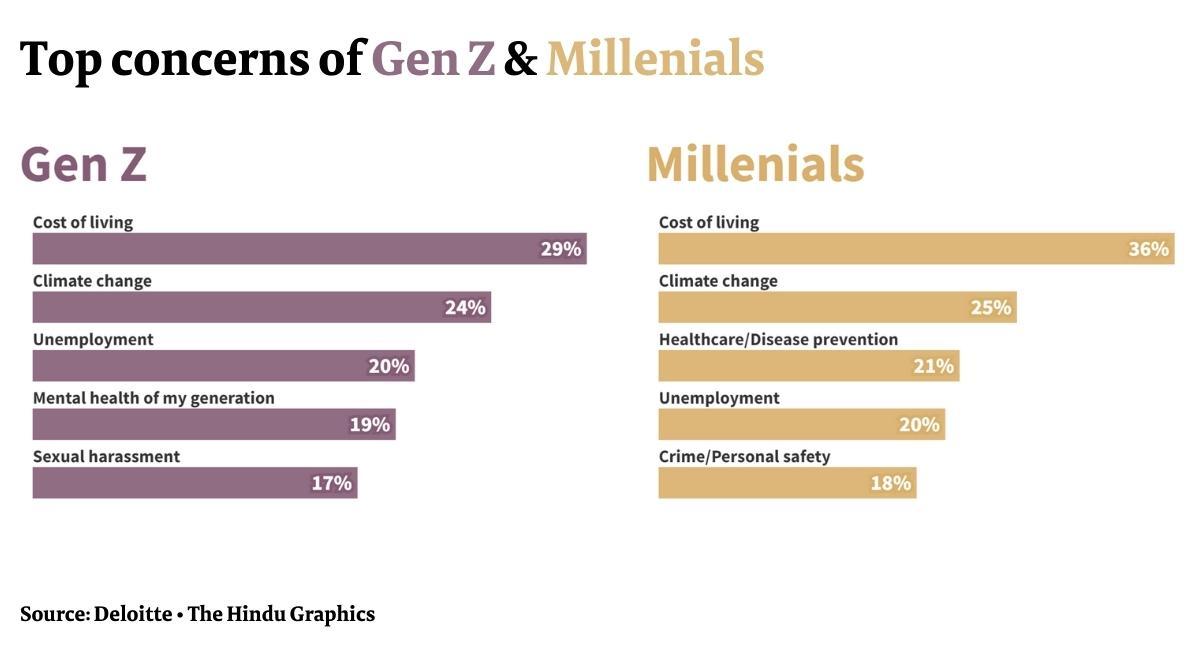

According to a survey by Deloitte, Gen Z and millennial workers are feeling “burned out”, and “many are taking on second jobs, while pushing for more purposeful—and more flexible—work.” The survey of 14,808 Gen Zs and 8,412 millennials across 46 countries, shows that almost half of Gen Z and millennials live pay check to pay check, and worry they won’t be able to cover their expenses. Over a quarter of the respondents were not confident they would retire comfortably.

Amid this financial unease, many of them are changing their working patterns with more of them opting for a second part- or full-time paying job in addition to their primary job, the report notes.

(For insights on emerging themes at the intersection of technology, business and policy, subscribe to our tech newsletter Today’s Cache.)

Go-slow movement

The new trend resonates with the old-time slowdowns and work-to-wage strikes. Mostly raised by labour unions a century ago, the ideas came from workers engaged in improving working conditions and increasing daily wage in factories and industrial units.

The ‘go-slow’ idea goes back to the late 19 th century when the organized dock workers of Glasgow, Scotland, demanded a 10% hike in wages. Their demand was refused by the owners, making the workers go on strike. To counter the budding movement, dock owners employed agricultural labourers to work for them. Dockers acknowledged defeat and returned to work under the old wage. The story didn’t end there. Dockers observed their replacements closely and found them to be inefficient.

Edward McHugh, founder of the National Union of Dock Labourers that was leading the protest for higher wages, said, “We have seen that they [replacement workers] could not even walk a vessel and that they dropped half the merchandise they carried; in short, that two of them could hardly do the work of one of us.” Based on this observation, McHugh told dockers, “There is nothing for us to do but the same. Work as the agricultural laborers worked.”

Dockers followed McHugh’s order to the letter, and after a few days the owners asked the union to tell workers to complete the task as before, and that they would be granted the 10% pay increase.

Around the same time, a similar protest broke out in Indiana, U.S., after railroad bosses cut workers’ wage. The protestors took their shovels to the blacksmith and cut two inches from the scoops. They returned to work and told their employer “Short pay, short shovels.”

Work in 2020s

Century-old dock worker and railroad employee strikes chime with our times on worker rights, fair wage and employee benefits. But, since the turn of twenty-first century, several aspects of work have changed. A significant number of processes are now automated. Robots have replaced humans in several industrial units. The labourer, too, has become a knowledge worker.

Their working day has expanded, and a significant amount of time goes in responding to emails and connecting with others over collaboration tools. These tools have increased the amount of time people spend in communicating with colleagues and clients spread across various parts of the world. Additional hours at work means less personal time.

The changes in work are a result of how companies re-organised for the information age. For example, a company engaged in a single activity branched out into other verticals. This shift made it focus on new customer segments, or in entering new geographies. These business decisions make it necessary for employees to connect with diverse colleagues to discuss and execute critical functions of the organisation.

Collaboration technologies in the workplace, adoption of matrix-based structures, and the proliferation of initiatives to create a “one firm” culture have created what some experts call the collaboration workload. “Too often, excessive collaboration harms organizational performance, overworking employees for only marginal gains,” Rob Cross and Peter Gray of the University of Virginia’s business school note in their paper titled ‘Where Has the Time Gone? Addressing Collaboration Overload in a Networked Economy’.

Collaboration overload

The duo’s research revealed that white-collar workers spend 70-85% of their time attending meetings (virtual or face-to-face), dealing with e-mail, talking on the phone or otherwise dealing with a barrage of requests for their input. Many spend so much time interacting that they end up carrying much of their work back home to be completed at night.

With more collaborative tools and greater demand for time, employee burnout has increased. Cross and Gray’s research was done before the pandemic. After COVID-19 and its resultant decision to lockdown and limit physical movement of people, the number of tasks done online has grown exponentially. While the increase in digitisation was seen as a boon during the early part of the pandemic, extensive reliance on technology has now become a bane for several workers.

Employee analytics firm Gallup said that the phrase “quiet quitting” caught on as “most jobs today require some level of extra effort to collaborate with co-workers and meet customer needs.” In its analysis of U.S. workers, the company found that the ratio of ‘engaged’ to ‘actively disengaged’ employees was 1.8 to 1, the lowest in almost a decade. The drop in engagement began in the second half of 2021, around the time when another hashtag went viral – – #GreatResignation.

But quiet quitting has nothing to do with quitting. It simply means that regular day-to-day tasks will be done. While there are always the ambitious, over-achieving few in any organisation, a large proportion of employees prefer to do the tasks they have agreed to do as part of their job description. And this does not mean quitting; it simply means they are working.

“Crunch culture”

This trend, however, may well be an anti-thesis of the infamous ‘crunch culture’. In the gaming industry, crunch is the word used for overtime. And during the period of crunch, which comes before an important deadline for a game’s launch, developers put in about 60+ hours a week. As per India’s Factories Act, 1948, a person cannot work for more than 48 hours in a week, and not more than 9 hours in a day. According to Section 51 of the Act, the spread over should not exceed 10.5 hours.

Most recently, videogame maker Striking Distance Studios’ founder and CEO Glen Schofield, said in a now-deleted tweet about the company’s upcoming horror title: “We r working 6-7 days a week, nobody’s forcing us. Exhaustion, tired, Covid but we’re working. Bugs, glitches, perf fixes. 1 last pass thru audio. 12-15 hr days. This is gaming. Hard work. Lunch, dinner working. U Do it cause ya luv it.”

That tweet drew a lot of negative replies, making him pull it out, and apologising for glorifying the long hours. “I’m sorry to the team for coming across like this,” he wrote later.

The crunch culture is not confined to the gaming industry. Closer to home, Shantanu Deshpande, founder and CEO of Bombay Shaving Company, drew flak for asking Gen Z to “put in the 18-hour days for at least 4-5 years” in a LinkedIn post. He noted that it was “too early” for young people to think about work-life balance.

Angry reactions on social media said he was promoting a toxic work culture. Deshpande apologised a week later, stating he should have been nuanced and given additional context in the post.

Deshpande is not alone in asking people to put in more hours. Several individuals replied to his post agreeing to his point on asking young workers to put in more hours. In 2020, Infosys co-founder Narayana Murthy suggested Indians work 64 hours a week for two to three years to compensate for the economic slowdown caused by COVID-19 related lockdowns.

A movement sans unions

Opinions of Schofield, Deshpande, and Murthy are shunned by a large proportion of young workers who are facing collaboration overload, compensation stagnation, and poor work-life balance. Instead, Gen Z and millennials are quitting quietly. But unlike the dock workers and railroad employees of the 20 th century, this crop of employees does not have an organised union to take their demands forward to find a lasting solution. At best, their digital movement sans the backing of a union can be a vent to their anger and frustration on crucial issues in today’s tech-enabled workplaces. But that expression alone cannot cure the malaise.

Perhaps, employers can address this issue by ensuring Gen Z and millennials get an enriching professional life. Creating a culture of good work-life balance coupled with appropriate compensation and opportunities to learn and grow in the current roles can enable a deeper sense of belonging for young workers. If done right, companies can reap a rich reward from their coordinated action as it can improve employee retention rate.

Deloitte’s survey found “an increase in loyalty” in young workers as many switched jobs over in 2021. This year, the report noted, millennials are more likely to say they expect to stay beyond five years rather than leave within the next two.