Refugee families and independent groups are preserving the memories of Partition with priceless objects brought from across the India-Pakistan border in 1947

Refugee families and independent groups are preserving the memories of Partition with priceless objects brought from across the India-Pakistan border in 1947

My first memory of the 1947 Partition is a borrowed one, of a James Hinks and Son oil lamp that sits next to my grandfather’s unframed, monochromatic photograph (dated September 3, 1933) with Thakar & Co, Karachi engraved on it. My grandmother, or biji as we called her, would always begin her Partition story with the lamp’s missing handle, which broke accidently on the day she left Karachi with her husband and a five-year-old daughter. She was six months pregnant then.

In great detail, she would explain how she hurriedly packed all her belongings in a trunk and took the lamp along when my grandfather’s friend and colleague at the Royal Air Force cautioned them about the possibility of riots spreading to Karachi. “It was a timely escape. The situation in Karachi worsened after we’d left,” she said, blessing and thanking the Muslim man who guarded them, along with two Sikh and Hindu families, through their journey to the port.

The lamp was a symbol of hope and resilience, but the Partition wasn’t. “Wealth can be made again, but the dead cannot be brought back,” she said, talking about the dear ones she had lost.

Relics from the largest migration in the history of mankind — ranging from jewellery, phulkari and watches to furniture, letters and utensils — carry the weight of 15 million refugees who survived chaos and separation. These objects are now being documented by the Punjab Digital Library (PDL), Partition Museum of Amritsar, and the digital Museum of Material Memory (MMM).

Public archives: The real picture

PDL has digitised over 17,600 letters and postcards sent to officers of the East Punjab Liaison Agency. In one letter, Lakshman Singh of Nankana Sahib asked Wazir Sahib of Gurudwara Shri Dukhniwaran Sahib, Patiala, for help, stating that 400-500 villages in Lyallpur had been surrounded by mobs.

A picture of the letter sent to Bashambar Sweeper, digitised by PDL

I’ll stay here in Lahore

A photo of a couple, attached with a letter sent to the chief liaison officer, was a rare find by Punjab Digital Library. In the letter dated May 28, 1948, Bashambar Sweeper’s wife had requested the authorities to evacuate him from Lahore, Pakistan.

He replied in Urdu: “Humne apni aurat ki chitthi ko padha hai aur padh kar faisla kia hai ki mai apni khushi se Pakistan mein rehna chahata hu. Mashroqui, Punjab mein nahi jaana chahta hu. (After reading my wife’s letter, I have decided to stay in Pakistan. I will not go to the divided Punjab).”

His statement, along with the photograph, was sent to his wife through the East Punjab Liaison Agency on July 29, 1948.

Letters and postcards sent in search and evacuation of separated brothers, mothers, fathers, sisters and daughters form another heavy chunk of the liaison agency’s records.

“It took seven years to digitise these records from the Punjab State Archive Department. No one has accessed these records before,” says Davinder. “ To tell our stories, we must save tangible memory. Technology can’t preserve deep memory. It can only be transferred to next generations through these objects. The way we remember decides the way we react. Material objects are one of the best ways to transfer memories to the next generation,” he adds.

Davinder’s family witnessed Partition too. His mother Manmohan Kaur, 75, still has a phulkari, a glass and a bronze tray that her mother brought with her from Pakistan, while his father Jasbir Singh, 84, cherishes his father’s pocket watch. “Waiting for the train to Amritsar at Railway Station Sillanwali, in September 1947, my father would anxiously look at his watch again and again. This was that watch,” says Jasbir. He remembers the violence of Partition like yesterday. “This watch was the only thing we got along , everything else was either lost, looted or locked up in a house we never returned to,” he adds.

Davinder Singh of PDL with phulkari and utensils brought by his parents during Partition; photo: Sandeep Sahdev

Personal stories: Knowing the past

“An object has the capacity to hold history, layer upon layer, generation upon generation, and eventually — as each generation creates new memories with the objects — become a palimpsest for family stories. The material, age, wear and tear of any object can speak to the time periods it has seen and in that sense, can act as a portal into history — familial, material, social, even political,” opines Aanchal Malhotra, who has written three books on Partition and co-founded the Museum of Material Memory with Navdha Malhotra .

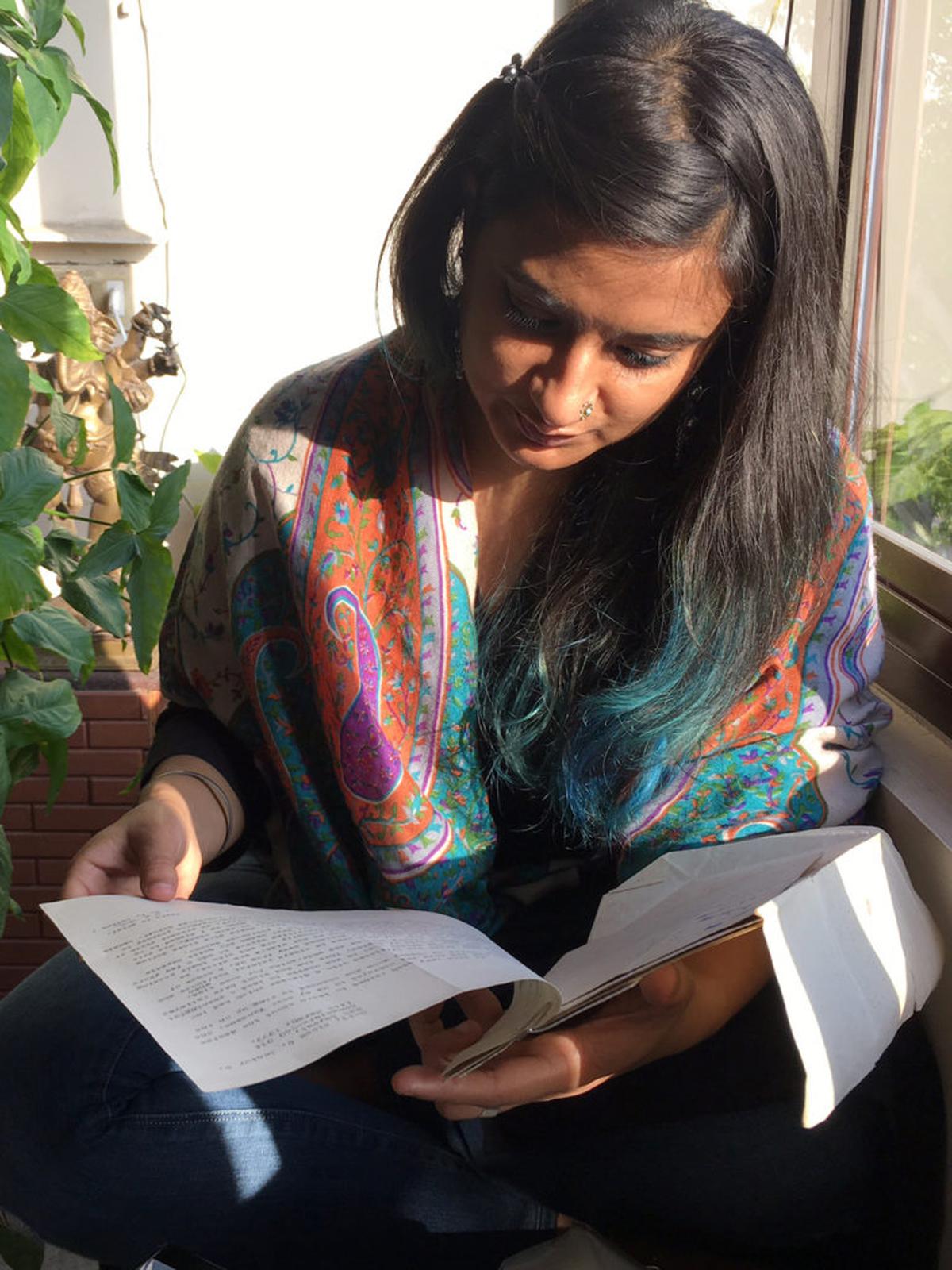

Navdha Malhotra goes through her grandfather’s documents; Photo: Special Arrangement

The museum is a crowd-sourced digital repository, tracing family histories and social ethnography through heirlooms, collectibles and antiques from the subcontinent. “At the beginning, we ourselves wrote many of the first stories. For instance, Navdha wrote about a grey briefcase that belonged to her grandfather, and I, about the silver coins that belonged to my grandmother,” says Aanchal.

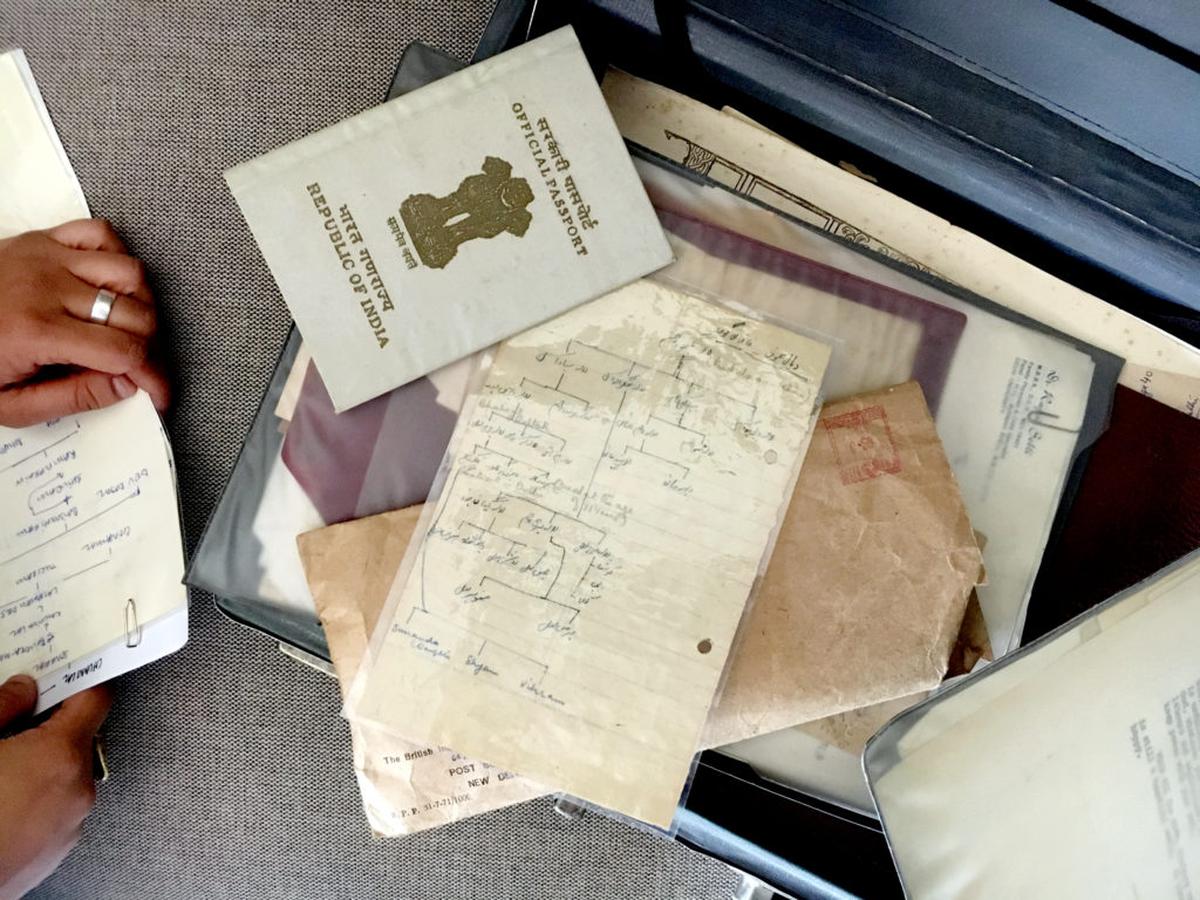

Navdha found her family tree in her grandfather’s briefcase, which also contained his passport, education certificates, receipts, pension documents and a political sufferer certificate issued by the Indian Government. “ My grandfather had Parkinson’s disease; I have no recollection of ever being able to understand what he said, because by the time I was old enough, the disease had worsened,” she wrote in her account.

The contents of Navdha’s grandfather’s briefcase; Photo: Special Arrangement

The sea of silver, originally published in Aanchal’s book titled Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory, is a story of how her memory engages with her grandmother’s experiences through a pile of one-rupee silver coins. Aanchal’s grandfather had passed away a few weeks ago and this was the first time she had seen her grandmother’s coin collection (1904-1947).

Aanchal goes through old documents with her grandmother; photo: Special Arrangement

While most museums highlight materiality and objects in a historical context, Aanchal feels they rarely provide a personal lens to the original owner and the memories that have been preserved within.

Visual history

The Partition Museum in Amritsar houses over 70 objects donated by refugees. The oral history of the objects draws a parallel connection with the object and its owner.

The Partition Museum in Amritsar

Kishwar Desai, chairperson of The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust, says, “We have been collecting oral histories and objects for seven years; it is a slow and steady process. Meetings with donors took place six years ago, when we were gathering material. One oral history would lead to another, and one donor would to another survivor.”

A new Partition Museum coming up in Delhi, at the Dara Shikoh Library, will contain a fresh collection, different from the one in Amritsar, she informs. The objects displayed at the existing museum include phulkaris, holdalls, trunks, a sewing machine, letters by Justice Teja Singh to his sons, a woman’s picture with her one-year old daughter who got lost during Partition, and even a briefcase.

Kishwar Desai at the Partition Museum in Amritsar

| Photo Credit:

Kishwar says as this was a physical museum, it was felt they could, at the time of collecting the oral histories, also gather material memory. “This has become a powerful memory of the period as the material donated was a testament to the cultural and social life of people. For instance, a letter written to family members when violence was imminent, a piece of clothing meant for a wedding which got postponed, a precious sewing machine which would be used to rehabilitate the survivors, or a utensil which was both, essential to cooking in the camps and a last remnant of home, added to the reality.”

History lost and found

Sunaini, shows the album which has a picture of her grandfather with Balraj Sahni; Photo: Sandeep Sahdev

| Photo Credit: sandeep sahdev

Everyday objects brought by refugees speak volumes about how the Partition was rushed. Most people left Pakistan thinking they would return, but only some did. Punjabi singer Surinder Kaur visited her home in Lahore in 1999, says her daughter Dolly Guleria. “In 1997, at Pittsburgh, US, an old couple gifted me a small album. It had pictures of a house where ‘mama’ lived before Partition. The couple said they moved into the house after Partition. When mama saw the album, she sobbed uncontrollably. The album is misplaced now,” she says. Her daughter, Sunaini Sharma (52), shares they still have an album of her grandfather which has a picture of him with Balraj Sahni. “It is from the early 1920s, during his college days in Lahore,” she says.

Picture of Sunaini’s grandfather (front row, second from right) with Balraj Sahni (front row, second from left); Photo: Sandeep Sahdev

| Photo Credit: sandeep sahdev

Kabir Singh, grandson of hockey legend, the late Balbir Singh Sr, says his grandmother brought along the first national championship medal of the three-time Olympics champion from Pakistan when he brought her from her home in Model Town, Lahore, to the Indian side of Punjab.

“He had presented it to her before their marriage (during their courtship) and she constantly wore it around her neck. In 1985, this medal and 35 other international and national medals were presented by nanaji to SAI (Sports Authority of India) for their now-shelved sports museum project, but these have been misplaced along with everything else pertaining to him, including his captain’s blazer from 1956 and over 130 original photographs,” he shares.

For Kabir, the medals are memories of his grandfather’s time leading up to the Partition, one of the reasons he has not ended the quest to recover his memorabilia even after 37 years. He says, “It is not the objects, it is the memories attached to him; they are priceless.”