Veteran photographer Sunil Gupta looks back at how the camera shaped his life, outlook and identity as a gay man in the 1970s

Veteran photographer Sunil Gupta looks back at how the camera shaped his life, outlook and identity as a gay man in the 1970s

What does it mean to be a gay Indian man? At 69, photographer, artist and activist Sunil Gupta, still hasn’t found an answer. “Or, it changes all the time,” he says.

When Sunil left Delhi with his family to migrate to Canada at the age of 15, his Indian past inched towards obscurity. It was the gay liberation movement of 1970s Montreal, and his discovery of the term ‘gay’ that pulled him closer to his identity. The camera played catalyst to this journey of self-discovery.

Documenting the movement, by shadowing marches on streets, camera in hand, he paved way to his own sexual awakening. Today, after decades of asking questions, learning, unlearning and silently evolving with his camera, while living with HIV, Sunil boasts an important body of work that reflects life as it is, and should be. He was recently in Chennai for a discussion titled Sunil Gupta: Practising for a Life, in collaboration with Chennai Photo Biennale and the British Council of India.

Sunil first picked up an old analogue German camera in the 1950s. To capture his childhood friend’s sisters, who happily posed as models, as they would for a magazine shoot. Soon after, he left suddenly to Canada. In those times, cinema was both a respite and education for him.

But enamored by the independence it gives, he returned to the camera. “I bought a film camera as a student, and started to shoot.. mainly the family. Then I got involved with the gay liberation movement in my university and made a tabloid for which started teaching myself photography. Not very good photographs…I was just trying to document what was happening,” he says.

Looking back

His collection titled Friends & Lovers: Coming Out in Montreal in the 1970s is a welcome collage of happy memories — of a carefree life painted with new-found hope, and liberation. A black-and-white frame shows three friends in the streets of Montreal, in the precipice of breaking out into a dance, happy to have found their tribe.

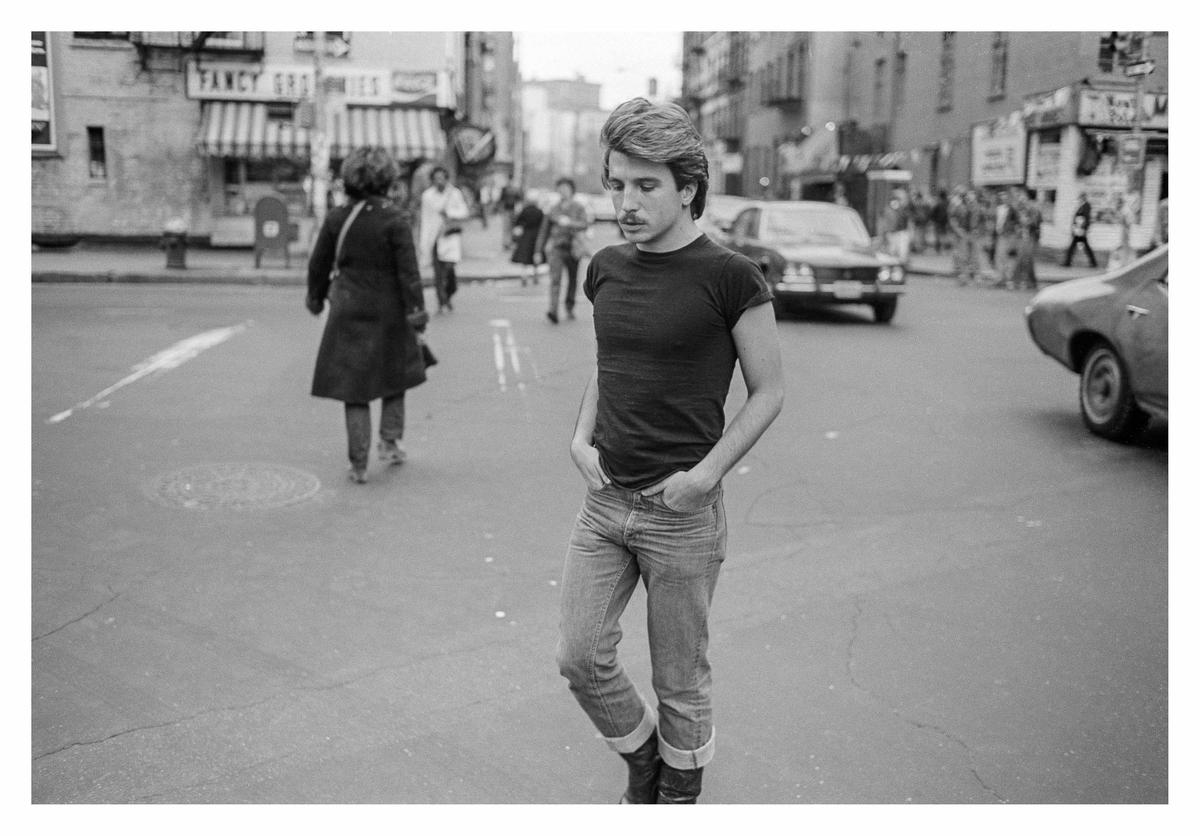

Another important moment in his personal history lies in New York where he documented a thriving “gay public space as hadn’t really been seen before”. He had originally gone to enroll in an MBA programme, but ended up learning photography with Lisette Model, who Sunil calls his mentor, in The New School, New York. “She pushed me towards photography and I took her word for it.” It was the days before the AIDS epidemic when everyone was young, busy and thriving, he remembers. Christopher Street, New York 1976, was a series that came out of the weekends spent “cruising with a camera”. It captures the city, its streets and people, characterized by infectious, youthful energy.

Sunil breaks the flow, to say that, cruising (to step out of one’s home to go and meet others) was something that gay men used to do everywhere in the world. “That has been replaced by the internet today, which has had a very disruptive consequence,” he opines.

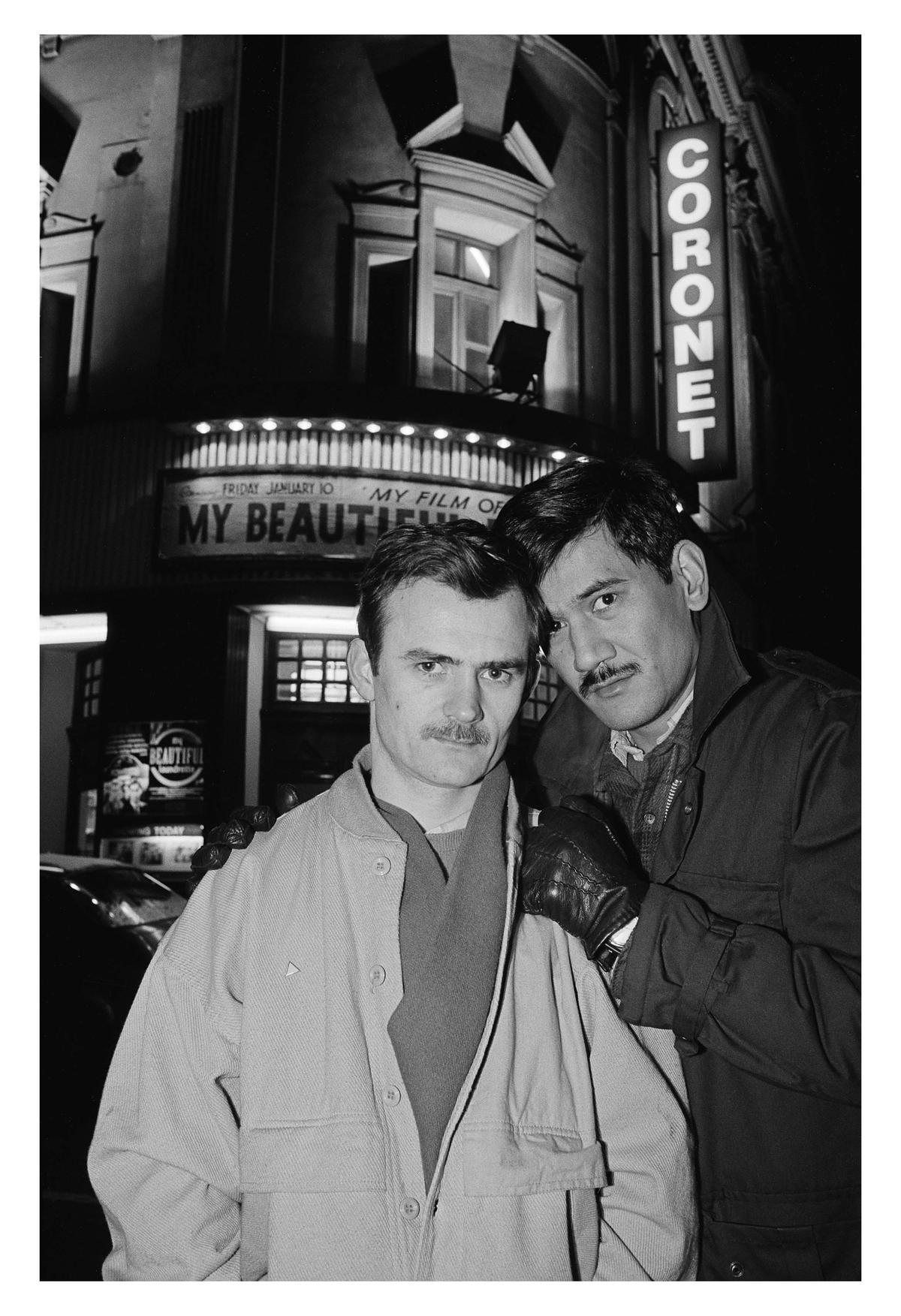

In the early 1980s, after graduating from the Royal College of Arts, he landed up in London, in the post-colonial world, “where everyone was reading Homi Baba and Gayatri Spivak”. Aesthetically, it was a postmodern world, he remembers. “I wanted to reach back to my Indian roots, by looking at the Indian interest in popular culture here.” This was also the time when he discovered the gay culture in India, which had its own language. In the ‘80s though, Sunil says his central obsession pivoted to race and representation. To lobby for Indian and African photographers who found it difficult to show their work, along with his peers, he founded Autograph, a collective that exists to this day.

Keeping it real

Taking on socially relevant issues through decades is no mean task. What makes photography the right medium to show these realities? “Primarily because it’s a representational medium which transcends any prior knowledge you need to decode it [the image].” He points to an example: “My initial post-college decade was spent around racial identity. And I feel self photography was the best medium for that because a picture describes it very clearly.”

From the series titled Christopher Street, New York 1976

| Photo Credit: Sunil Gupta

Over time though, both Sunil’s practice and the issues he addresses, have evolved. “Initially, I saw them in a very simplistic way. I was modelling myself in a 1950s photography style, to have a more humanistic, social change-outlook.” In the ‘80s however, when he got his arts education, and travelled to India and looked closely at social issues like institutional poverty, he started questioning the purpose of social documentary and the running risk of it being voyeuristic. “As a practice, it became untenable.” His approach too, changed. Today, he admits to still learning and unlearning about the issues he talks about.

From Delhi to Montreal to New York, back to Delhi, and to London (which is home base now), Sunil’s camera has seen the realities of the LGBTQIA+ movement across cities and countries. He does not believe in the concept of a permanent home. He says, “In a nutshell, home is in my head. It is not a physical place. It travels with me. It’s in the human relationships that I have been nurturing over the years.”