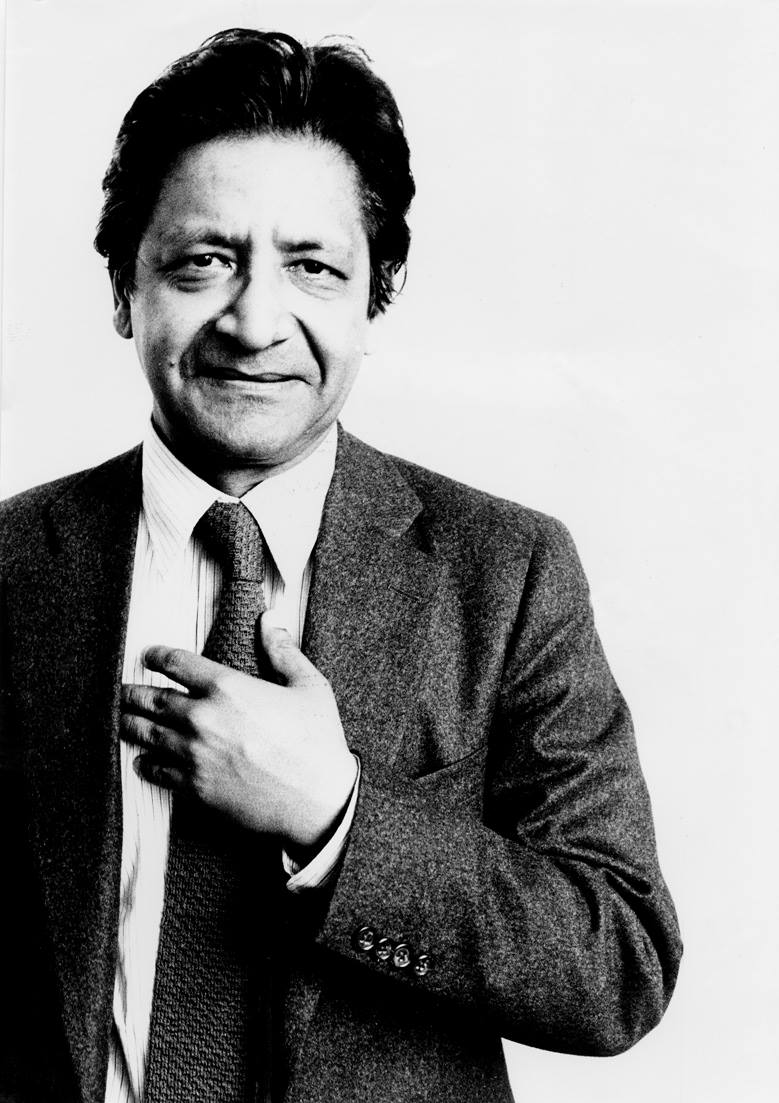

With his second book India, Bharat and Pakistan: The Constitutional Journey of a Sandwiched Civilisation on course to become a bestseller, J Sai Deepak’s arguments for a civilizational understanding of India finds more and more takers each day. The conversations are not in the fledgling stage anymore. In fact, they never were. Deepak says his outlook towards the history of India draws heavily from the writings of Aurobindo Ghosh and Swami Vivekananda.

In a freewheeling chat, he talks about his career as an author, the unknown facts of the Independence movement that need to be reckoned with, the evolution of VS Naipaul’s views on India and the role of cinema in Indian society. Excerpts from an interview:

You’ve been vocal about many issues on TV debates and lectures. How have you coped with that fame that followed?

Without sounding clichéd I am fairly comfortable with public debates and speeches. That has been my track record since my schooling days. It just so happened that my choice of engineering was inconsistent with that track record. I was not as if I was pushed into engineering, I certainly took it up because it was a subject with a lot of interest. By the time I was done with engineering, this much was clear, that I wanted to be in a particular profession that allowed me to explain my position with a fair degree of confidence and training. Anybody can have an opinion, but it is important to have a qualification under your belt which informs the opinion that comes from you. Therefore, the transition to law, in my experience, was fairly logical considering what I wanted to do. I was, remain, and will always be a lawyer. I see the book-writing activities as an extension of my professional commitment simply because I remain within the bounds of law where I speak of the constitution. The only difference is while most people simply look at the subject of constitution primarily from a legal perspective, I am saying that there is a civilizational aspect to it, there is a cultural aspect to it, there is a historical aspect to it, there is a politico-scientific aspect to it, all these will have to be weaved together to arrive at a particular constitution. Therefore the books are a culmination or convergence of history, political science and law.

One of the prerequisites before reading your second book is to let go of blind faith towards any personality. Was this something that you had to do as well while writing it?

Most people go through a certain transition in their lives regardless of who they are. The clear blacks and whites in your life gradually move towards grey as you grow old. That maturity happens in general. That automatically changes your perception in every level towards a subject, history not being an exception to this rule. So, the sense of idealism that I may have had perhaps 10-15 years ago is not the sense of idealism with which I look at history anymore. I am simply saying people are mixed bags therefore history has to be a mixed bag. At the outset I had no preconceived notions by the time I started writing the second book. I told myself that let the information shape the opinion. Of course, there are a certain set of biases which are ideological in nature. I subscribe to a very specific school of thought which I will never give up. Therefore you’re looking for facts that feed into the preconceived notion. That’s when the mind has to push back and say don’t succumb to conformation bias. When contrary information presents itself you have to deal with it. That’s the first bit, and two, even the tallest of our heroes; how they may have led down the civilization at crucial junctures when the chips were down is a lesson which I think needs to be taught. Well taught sounds condescending, let’s say shared.

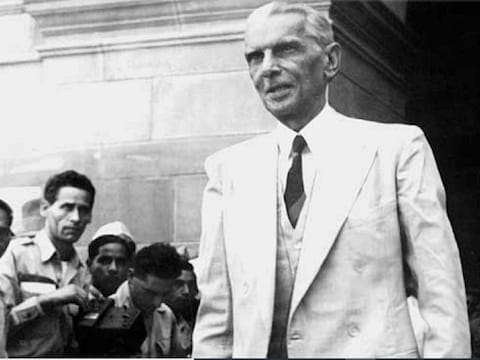

One of the many myths that you bust is that of Mr Jinnah and how he was a secular leader pushed towards the Pakistan faction. You reproduce texts that clearly show his biases when he held dual membership of the Congress and the Muslim League.

Very few people have to patience to look into the primary sources. Therefore I have gone to the proceedings of the Muslim League and Congress to see what is it that they have said. And where are we getting these received wisdom from. Perhaps, an example from my own profession will help. There are judgments and there are books that summarize the judgments. I rarely read a law book, because that is an interpretation of the author of a particular judgment therefore I prefer to read the judgment directly. Only when I believe that a particular question hasn’t been answered do I look at a law book for an ease of reference because the appendix gives you a ready reference to something. I have brought that particular experience to bear in my reading of history. Not to say that there are no secondary propositions here. What I have done is to rely on extensive PhD thesis. This is because as a part of PhD thesis you undergo a much more rigorous process as compared to the publication of a mainstream book because you’re going to be subjected to a lot of internal and external validation there. I have relied on that and have looked for their footnotes to see what are they saying. The subject is already sensitive and I don’t want to be accused of either plagiarism or for that matter distorting history or paraphrasing it in a distorted fashion. The strategy of extracting primary sources continues here as well. When I deal with a sensitive subject like the confluence of religion into politics, that strategy is even more relevant. Therefore it has worked really well. I am confident that the history department across the board will now have to re-evaluate the way they have presented Bharatiya history to the students.

Should Indians concede that Mr Jinnah won?

I have said so before. Given his intention, he partially won. Assume for a moment, you have a home. Your victory cannot be that you have lost only one third of it. The fact that you have lost one third is your defeat. And the fact that he moved from zero to one third is his victory. His aspiration may have been hundred percent, but he landed with 33% still goes to his benefit. That’s how I would see it.

The second talking point is the Mopilah Riots. Recently a film was which was to be made on the same was shelved due to public outcry. Are your efforts bearing fruit?

I won’t take remotely any credit for this because for someone to make a movie on Moplah Genocide and that too in Kerala under the current circumstances, the credit goes entirely to that gutsy person whoever did this. There were multiple reasons that I felt that this episode needed to be captured in greater detail. One being last year in September, as part of Dr Shashi Tharoor’s book launch there was a debate in Chennai where this issue came about. He presented it as a peasant rebellion and perhaps as a rebellion against colonial establishment. That was not the entirety of the picture or even the true picture. And I said as much there. And since the theme of this book gave me an opportunity to address this issue in some detail, I chose to go all guns blazing with all the primary literature being quoted there.

A time has come where the society is ready for uncomfortable facts no wonder the clamor for changing the history syllabus of this country is growing with each passing day. So there is a fertile ground and a receptive audience which is waiting to consume this receptive information. It is upon people to latch on to this particular opportunity and push as many facts through this window that has presented itself. So that these inaccuracies can be set right.

Where do you see your works with respect to the likes of Sri Aurobindo, Swami Vivekananda or even Mr Gandhi and Mr Nehru?

My book is in principle a negation of everything that Mr Nehru wrote. There I will not beat around the bush. There may be partial overlaps with Mr Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. But there ends the issue. Any of those overlaps are at best coincidences. Nothing which is intended. I certainly believe that my works are a reflection of the teachings of Sri Aurobindo and Swami Vivekananda. In the first book, I could have directly begun with their works as the basis for Bharatiya decolonial exercise. When the Indian mind is buried under the influence of the West it requires a compare and contrast exercise for it to be able to consume something that is Indian. You will consume yoga because it has become cool in the West. Until then, I have heard people, even the educated elites in this country call it uncle yoga. Today the world’s best athletes are resorting to yoga. The point was to draw a particular literature from that sphere of influence where the mind is currently engaged in and say okay this I what the literature says. Now, let me present to you something that is native. Now, tell me why are you accepting this and rejecting this.

How do you view Mr VS Naipaul’s works? He did write extensively about the Hindu civilization and what became of it.

I think Shri Naipaul presents a very curious picture. His heart was certainly bleeding for the Hindu civilization. That much is clear. That he saw it as a wounded civilization is not a wrong assessment. His visits were predominantly in the pre-liberalization era. Therefore what he was looking at is the Nehruvian-Marxist setup of growth rate and everything else which he ended up assuming is a reflection of the native society’s inability to catch up with the West when in fact it was an artificial fetter. His works start taking a slightly different tone post liberalisation where he realizes that perhaps his assessment was incorrect. He openly talks of the destruction cause by Islamic invaders as far as Bharat is concerned and to that extent you must give him credit. If he was moving in these Western circles and fashionable circles, he could have comfortably mouthed the very same leftist version of the Bharatiya history. He chose to come out differently. His reactions to what happened in 1992 were very clear in terms of where his allegiances lay. That cannot be denied. Therefore I would say that his was a case of gradual evolution where he was open to recalibrating his position. So I am not going to be particularly uncharitable and stringent in my analysis of Mr Naipaul. I’d still say his heart was in the right place.

You’re someone who understands the importance of cinema. You’ve spoken why Kashmir Files was an important film. How do you the future with respect to cinema?

It is going to be a glorious tussle between a bunch of wokes and a bunch of Bharatiyas. I want to watch what this produces in terms of both artistic expression and the social service function that art performs. Be it RRR, Kashmir Files, Tanhaji or even Bahubali for that matter. They’re all signaling something very different. I just hope it is not merely someone cashing in on the blowing wind and looking at an economic opportunity at civilizational expense. I am keenly looking forward to it. I may even disclose this that some directors and superstars from the South have shown interest in the content of my first and second books.

Watch the complete interview here: