Director David Lancaster opens up on Speed is Expensive, a movie on Phil Vincent, the flawed genius behind Vincent Motorcycles.

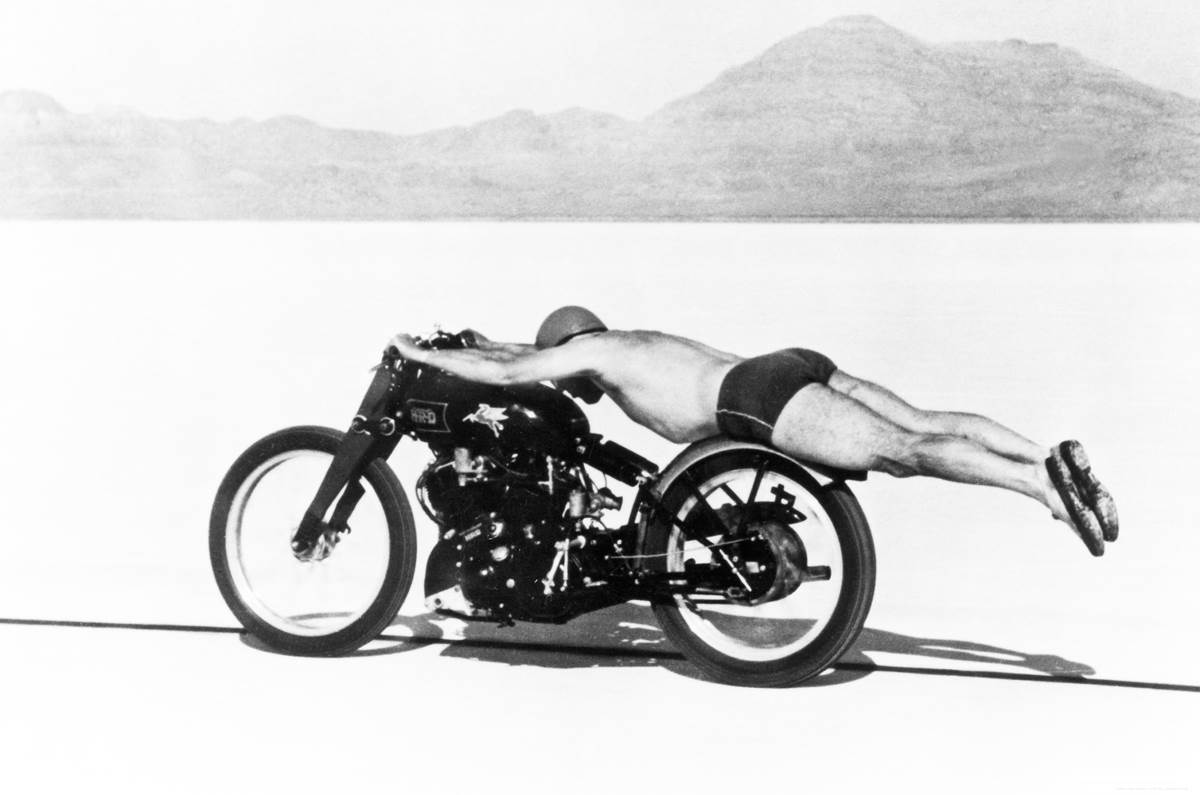

In 2018, Bonhams sold a 1951 Vincent Black Lightning for $929,000, making it the most expensive motorcycle ever sold at an auction. Setting records is a very Vincent thing and so are inspiring superlatives. The Black Lightning, a racing version of the Vincent Black Shadow, the first ever ‘superbike’, was the world’s fastest production motorcycle in the post-war years. In 1948, American motorcycle racer Rollie Free achieved an average speed of 150.313mph (241.905kph); two years later, he would return to obliterate his own record, touching an average speed of 150.58mph (242.335kph). In 1956, in New Zealand, a Vincent set a new speed record at 186mph (299.338kph).

Rollie Free stretched out over a factory tuned Vincent Black Shadow at the Bonneville Salt Flats, on his way to a record 150mph. Courtesy William Edgar archive

Vincent Motorcycles’ advertisements in the early 1950s proclaimed: ‘The World’s Fastest Standard Motorcycle. This is a Fact Not a Slogan.” Vincent might have made big-bore, high-performance motorcycles, but they were not all only about speed. The motorcycles were also built to exacting standards, using materials such as magnesium alloy; Vincent’s innovations included a cantilever rear suspension (an early version of the monoshock) and the chassis-less construction of the post-war Series B Rapide, which inspired engineers such as John Britten half a century later.

Compared to the likes of Triumph and BSA, the company produced very few bikes annually, but they cost twice as much as products from other British motorcycle companies.

If you are an enthusiast, especially a classic motorcycle lover, you probably know everything about its story that began with the purchase of HRD Motors in 1928 and ended in 1955. But what of Philip Vincent, the driving force behind the motorcycles? In ‘Speed is Expensive’, which premiered at the Barnes Film Festival in June, David Lancaster takes an unflinching look at a temperamental, stubborn engineering genius who was born into wealth and educated at Harrow and made, as a line in the film goes, “motorcycles nobody needed and few could afford.”

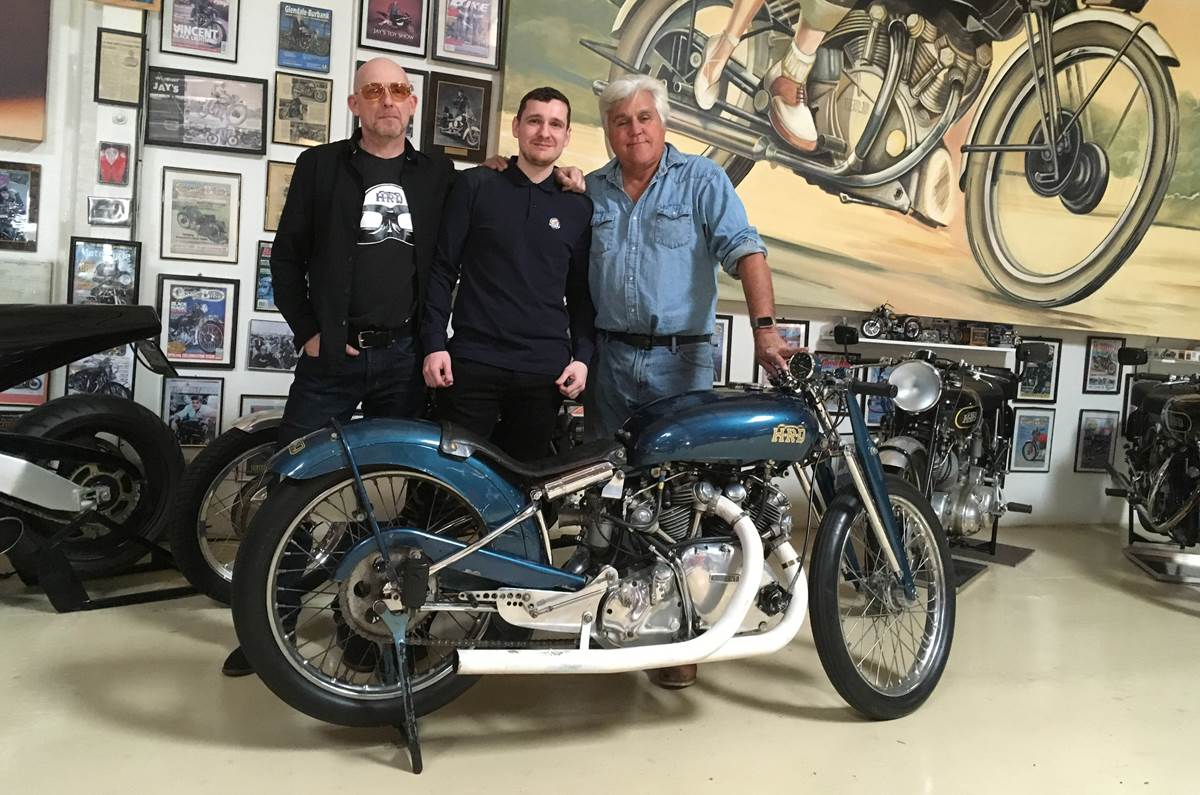

The documentary is narrated by Ewan McGregor and features Vincent owners such as television host and comedian Jay Leno, The Clash bassist Paul Simonon, and John Surtees, a former apprentice at Vincent and the only man to have won world championships while racing motorcycles and automobiles.

David Lancaster with Phil Vincent’s grandson Philip Vincent-Day, and Jay Leno

Here, Lancaster, who teaches journalism at the University of Westminster, speaks to Autocar India about the making of the movie and getting to know Phil Vincent better.

When did Vincents come to dominate your life?

Probably quite early. My father owned a Vincent Series B Rapide, which is the motorcycle I now own, and my parents, too, several trips into Europe. Vincents weren’t worth as much money or super special in the 1970s; they were just fast, old motorcycles, but just motorcycles.

What did directing a movie on Phil Vincent’s life teach you about him? What sort of a man was he?

He was – I came across this phrase a few years ago – an ‘emperor entrepreneur’. Because of his fairly wealthy background, he was able to buy the rights to HRD. He was making motorcycles at the age of 19 and he never really worked for anyone else. He went to Harrow and had this amazing self-confidence and determination to unfold his own ideas. If you look at a Vincent, you know it’s built very differently. Vincent and his design partner Phil Irving created motorcycles without any thought about what will cost money and where they will make money. It was completely different to BSA and Triumph, for instance, which had this hierarchical structure, with a board of directors and all that. But after his crash in 1947, he was a changed man. John Surtees says that today, it would be termed post-traumatic stress disorder, but in those days it was, sort of, dust yourself off and get on with the job. He was also a bit of a gambler. He gambled his family’s money away on developing the bikes in the 1930s and again gambled significantly on the fully enclosed Series D, which was a resounding flop. The irony is that most large motorcycles today are fully enclosed. He was way ahead of his time. The trajectory of his life after 1955 was quite said. He never designed another vehicle that would go into production. But he always had ideas. He had this idea to make a rotary engine using ceramic materials and he did build a prototype. He knew emissions from standard piston engines would be a problem and saw rotary as the way forward. In a way, Vincent, the company, was a lot like Bentley. When W.O. Bentley was in charge, they weren’t distracted by making money. They just wanted to build beautiful cars.

He attracted the best of talent. Was he a charismatic man?

He clearly had the ability to inspire people. Vincent never paid the highest wages, but people wanted to work there because it was an interesting motorcycle to produce. It wasn’t a BSA Bantam. John Surtees has worked with the likes of Enzo Ferrari and Soichiro Honda, and he put Phil Vincent right up there along with these men. He might have not made the impact like Ferrari or Honda, but what he did was completely different.

Murali Menon

Follow @speed_is_expensive on Instagram for updates on the release of the documentary.