Today, many people, including designers, fear losing their jobs to artificial intelligence (AI), and generative AI. Norman, however, sees this as a “great opportunity” for designers to lead the way and demonstrate how AI can be developed differently than it is now.

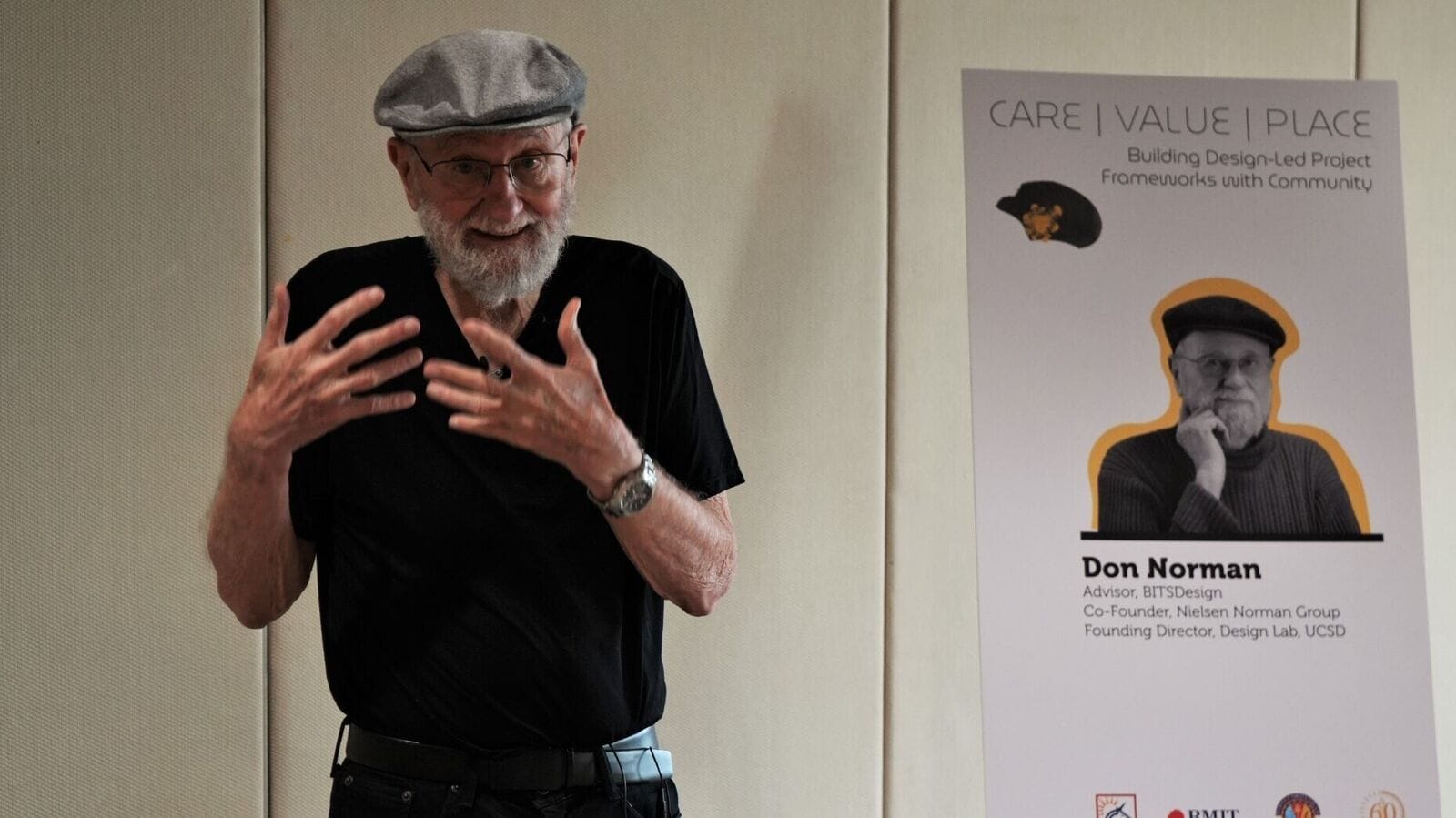

“As the head of a company or chief design officer of a large company, designers have to do what they’re told to do. I’m saying ‘No’,” 88-year-old Norman asserted in an interview during his visit to India last week. He reasons that designers are creative and “should be determining what needs to be done.”

Norman adds, though, that to take on this challenge, designers would need a broader education. He walks the talk with degrees in engineering and psychology.

There’s no such thing as a perfect design.

“I understand technology and people, and how business works, having been an industry executive. I’ve also gone to Congress in the US to try to get the first Wi-Fi band and other standards. And I understand how politics works,” he elaborates.

Norman says he’s trying to change the way design is taught. His goal is to help schools worldwide to become accredited to focus on humanity-centred work.

“At deemed (autonomous) universities, you have the freedom to teach in innovative ways, unrestricted by government mandates. That’s why I’m at the BITS School,” says Norman, who is a former vice-president at Apple, founding director of the University of California Design Lab, co-founder of the Nielsen Norman Group, and advisor to the Mumbai-based Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS) Design School.

Impact on environment

Norman has written 21 books, including ‘The Design of Everyday Things and Emotional Design,’ translated into 25 languages. According to Norman, the design principles defined in ‘The Design of Everyday Things’ (the 1988 version was titled, ‘The Psychology of Everyday Things’) remain unchanged since they are about human behaviour. The only change is in the different examples provided to cover newer technologies.

“What’s missing, however, is what is not in the book, since we completely ignored the impact upon the environment — we were destroying cultures, lives, the world, and all living things. So, the humanity-centred design envisages concern for the environment and for cultures, and for all living things,” he says.

His latest work, ‘Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity-Centered’, which was published in March 2023, covers these topics. That said, how does one differentiate between human-centred, and humanity-centred, design?

“I call human-centred design ‘HCD’, and I call humanity-centred design ‘HCD+’ because they follow the same principles, but the latter is more expansive,” says Norman.

He cautions that we “should not be colonialists when we teach designers.” And Norman does not see much value in sending anthropologists or ethnologists to figure out what problems the world’s 8 billion people are facing.

He says that people already know what their problems are, and we should be helping them with knowledge instead of telling them what to do. If they need new sanitation or clean water or healthcare, we could “provide them with some expert knowledge.”

Norman calls this “participatory design or co-design” in his latest book. He says this approach “should be a fundamental part of design.”

Norman rues that large companies like Apple and HP, “where I have worked,” now prioritise profit over sustainable design. According to him, they create products that are difficult to repair or upgrade, contributing to environmental waste.

Any discarded product with a plug or battery is considered electronic waste, or e-waste. Since these discarded devices contain toxic additives or hazardous substances such as mercury, which can damage the human brain and nervous system, they are health and environmental hazards. E-waste generation is rising by 2.6 million tonnes annually, and will reach 82 million tonnes by 2030, according to the UN’s fourth Global E-waste Monitor released in March.

To address this issue, Norman suggests adopting the circular economy approach wherein materials are reused, upgraded, and designed to last longer, mimicking natural processes.

Products vs services

Acknowledging that companies argue that longer-lasting products hurt their business model, Norman suggests that one solution is to shift from selling products to offering services. Every product, such as a laptop or camera, essentially provides a service—whether enabling communication or capturing memories, he explains.

He emphasises that a service-based economy could extend product life cycles, offering consumers subscriptions instead of disposable goods.

“While some people dislike subscriptions, we already pay for services like electricity and water,” he points out. Norman believes that transitioning to a service economy could happen gradually over a decade, benefiting both businesses and the environment.

That said, does Norman today consider Apple to be an innovative and cool company in terms of design?

“I joined Apple after Jobs left and worked under the then CEO, John Sculley. Apple was struggling then, which turned out to be a valuable lesson for me. You don’t learn much from success, but failure teaches a lot,” he recalls.

When Apple founder Steve Jobs returned, he shuttered Norman’s group called the ‘Advanced Technology Group,’ “which made sense as we were focused on long-term research.”

“Many of our innovations still exist in today’s Apple products, and my team quickly found new roles at IBM and Microsoft,” he says with a smile.

The key lesson he learned at Apple, says Norman, was that having a great product isn’t enough—how it’s perceived matters more. People form opinions based on impressions, not necessarily on reality, and Jobs initially failed to understand that.

…if you take a look at the new work in AI, it is very powerful today but also has a huge number of weaknesses, which actually is a good opportunity for us.

“When Jobs returned, he was wiser. I called him “Steve Jobs 2.0″—he had learned from his mistakes and ultimately saved Apple. However, in his pursuit of beautiful industrial design, Apple’s products became harder to repair and use,” rues Norman.

He adds that Apple, like others, has now lost focus on usability, making products that look great but are increasingly difficult to use and understand.

Meanwhile, the design field has expanded significantly to include digital, AI-driven, and even autonomous systems. When asked how UX designers should adapt their approach to keep up with these technological shifts, Norman said it was a “bad” idea to do so.

Lead, don’t follow

“You shouldn’t adapt to these new technologies — you should be leading the way. You should be designing these technologies and making sure they are appropriate for humanity. Because if you take a look at the new work in AI, it is very powerful today but also has a huge number of weaknesses, which actually is a good opportunity for us. So, I think designers should be at the forefront and ought to be thinking how they could use some new principles,” he said.

Norman highlights the ongoing technological revolutions transforming industries. New sensors can monitor body conditions and satellite data, while materials like carbon fibre and advanced manufacturing enable stronger, lighter products with less waste.

Digital twins allow real-time monitoring of factories, and AI enhances areas from photography to robotics. Given these advancements, Norman urges designers to focus on user research, understanding all stakeholders from end-users to manufacturers.

He emphasises the importance of testing and iteration, noting that “there’s no such thing as a perfect design.”