The cookbook features dishes dating back centuries and also has an illustrated section where readers can document their own recipes

The cookbook features dishes dating back centuries and also has an illustrated section where readers can document their own recipes

When Shruti Taneja lost her mother a few years ago, she came to the realisation that sometimes, with the passing of one person, an entire culinary repertoire can disappear. And so she created Nivaala, an illustrated recipe journal that encourages young people to document their family recipes before they are forgotten.

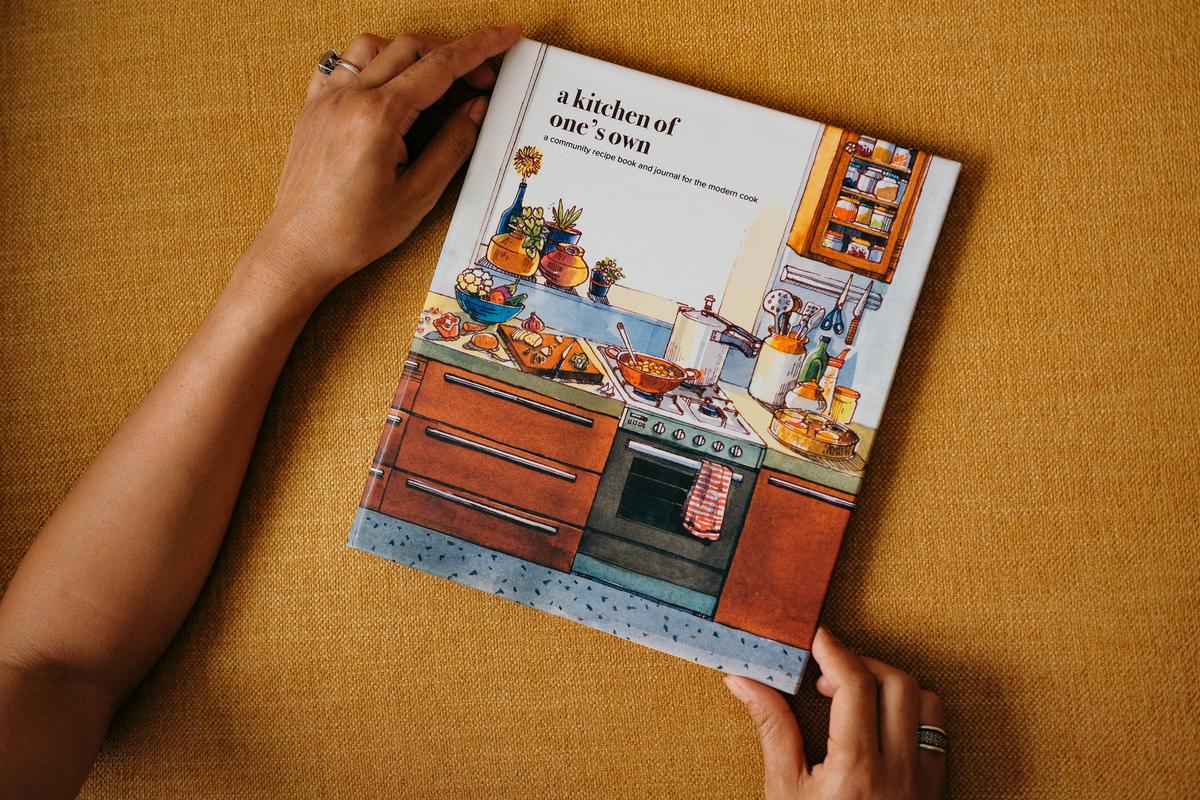

At Goya Media, a digital venture centred on storytelling around food, founders Aysha Tanya and Anisha Rachel Oommen had a similar vision — of documenting heirloom recipes from home kitchens across the country. A Kitchen Of One’s Own, their collective cookbook scheduled to be published next month, is an amalgamation of the passion that both Nivaala and Goya Media have for preserving culinary heritage and making it available to the modern day cook.

“When we conceived Goya six years ago, we wanted to celebrate the home cooks of India,” says Tanya. She believes India’s real culinary tradition is hidden in home kitchens. “ A Kitchen Of One’s Own is the realisation of a dream we have nurtured, and brings together recipes collected over the past six years.” These recipes, many preserved only in oral tradition until now, represent the staggering diversity of India’s food landscape.

From Sri Lanka via Myanmar

Take for instance the 200-year-old Tamil Muslim recipe of thakkadi. Thakkadi originated in Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu and is believed to have travelled from Sri Lanka via Myanmar, where men from the trading communities of both countries often travelled to. Made with tender mutton pieces cooked with rice-flour dumplings, it results in a thick, hearty gravy, and the dish is little known outside of the community, making it “definitely worth preserving”, says Tanya.

The highlight of the cookbook is recipes with unusual ingredients such as jute leaves, poppy seeds, and mutton fat; their origins in India’s layered history of colonisation and Partition; and provenance. The Bengali paat shaak’er jhol recipe that features tender jute leaves crossed over from East Bengal, now Bangladesh, during the Partition. Paat shaak is essential to summer lunches in typical Bangla households but is becoming rarer today because the leaves are grown only in Bangladesh. Families that migrated however have kept the tradition alive with the little that comes in from the neighbouring country every summer.

Rui poshto, another Bengali recipe, finds its roots in our colonial history, where forced cultivation of poppy for opium trade left farmers so impoverished that they had nothing but poppy seeds, the dried waste of opium plants, left to cook with. Today, poppy seeds have become Bengal’s distinct culinary identity as has rui poshto — a dish of rohu, a freshwater fish abundant in Bengal, cooked with ground poppy seeds.

Garhwali tea, made with yak milk, dried peach, salt and sun-dried mutton fat, is a recipe carried on in oral tradition.

Meanwhile, the Garhwali tea, a fascinating mountain tradition in Dehradun, documents a local recipe where a unique salty concoction is made with yak milk, dried peach, salt, sun-dried mutton fat, and sometimes, even ghee. It doesn’t find mention in cookbooks but is a recipe carried on in oral tradition.

900-year-old roti

The curators have taken special care to represent all communities, including the diaspora and the marginalised. Ranya roti of the Mahars of Nagpur is one such. The first mention of the roti is found in 13th century writings of Marathi philosopher Sant Dnyaneshwar — which makes the dish at least 900 years old.

The ingredients and method of cooking are unique — it is made with lokwan, a sweeter variety of wheat, and the dough is kneaded to a slimy, glutinous mix, then hand-rolled into translucent large rotis and cooked over inverted clay pots. The baked bean curry, a recipe that is often looked down upon for its simplicity, represents the diaspora in South Africa and how they adapted to local ingredients when they could not find their own.

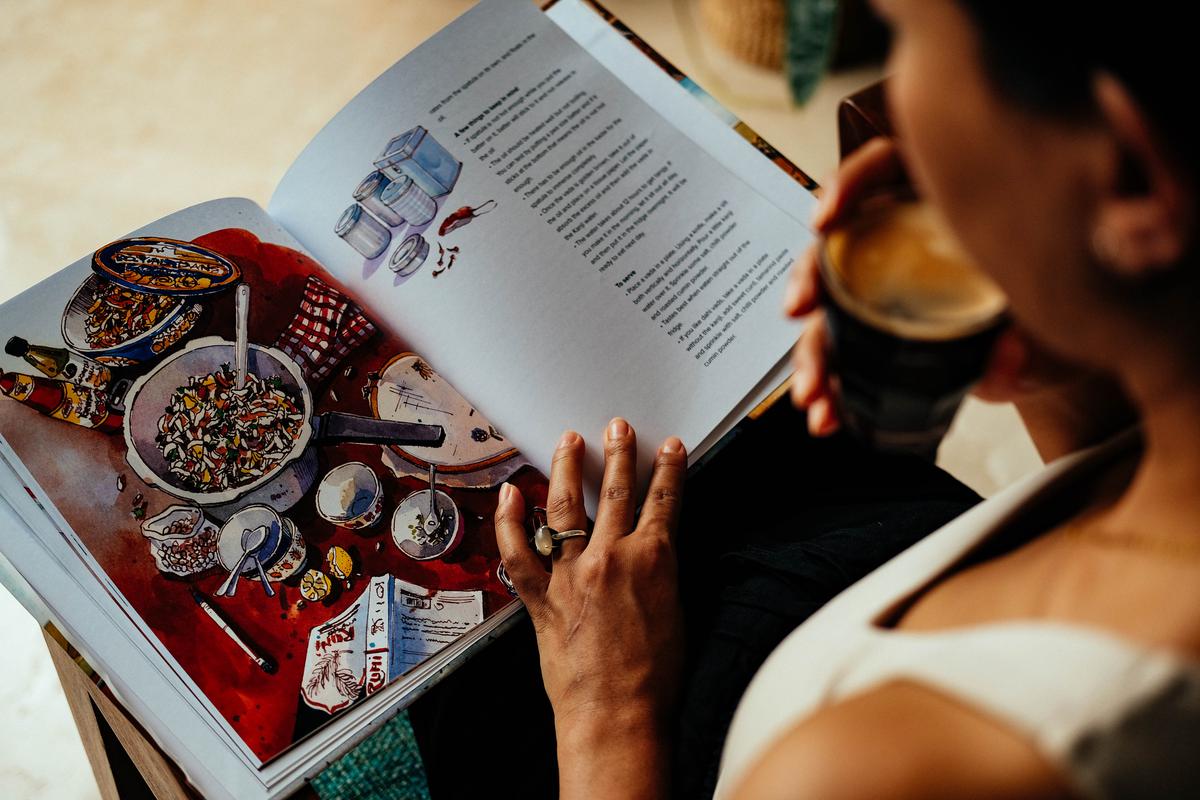

The cookbook has beautiful artwork by Zainab Tambawalla.

| Photo Credit: Goya Media

But who is the book for? “It is for everyone who is interested in food,” says Taneja, who has also designed the book. According to her, writing down family recipes makes them all the more precious and tangible — something you can pass on to future generations. Which is why the 110-page cookbook comes with an evocatively illustrated section where readers can document their own recipes.

While the recipes are precious, no doubt, it is the artwork by Zainab Tambawalla that sets A Kitchen Of One’s Own apart. “Zainab would look into the story behind each recipe; into the elements that represent each community, and then bring them into her art which lends a beautiful texture to the book,” says Oommen of Goya Media.

One look and you know what she means. A barni of pickle on the counter, brass masala dabba by the stove, a sink filled with dishes — the evocative illustrations take you to the kitchens of the past.

And it is this past — and the need to bring it to the present — that is at the core of A Kitchen Of One’s Own.

The Delhi-based writer-consultant is interested in food, travel, culture and design.