Deepti Naval’s A Country Called Childhood is both a memoir and a commentary on life in the late 20th century

Deepti Naval’s A Country Called Childhood is both a memoir and a commentary on life in the late 20th century

Deepti Naval’s new book, A Country Called Childhood, has a unique quality of specificity and universality. At one level, the noted actor-author-painter’s work is an autobiography — an understandably indulgent look at innocent early years, of days spent playing with her elder sister, Bobby, and nights spent snug under a quilt with a book, at her home, Chandravaali, in Amritsar. It is about girls and their impish charm, and the little escapades to watch the latest Rajesh Khanna or Shammi Kapoor starrer at the cinemas.

On the other, it beautifully paints the picture of Amritsar in the 1950s and 60s, a city at peace with itself. She brings out the crevices and craters of the city’s socio-cultural canvas: the plight of a well-educated middle class man and his inability to get a job according to his qualification; a city where Brahmins interact with the cobbler community, but from a distance; of living next to a mosque — she calls it maseet (for masjid) in the typical Punjabi way — where the muezzin extended an invitation for prayer through his azaan and where, unlike now, women worshippers were welcomed.

A Country Called Childhood

The book begins with her birth on a stormy night in 1952, and the readers travel with her to the U.S. (following her father, who had left a little earlier) and immigrant life across the seas. And, of course, there’s much dedicated to what inspired her to get in front of the camera (though she recalls her grandmother admonishing her, ‘Little girls from good families don’t ever go to cinema on the street”).

Naval, 70, takes a few questions from The Hindu’s Sunday Magazine. Edited excerpts:

The book is an autobiography and an essay on Amritsar, and the Indian society that was.

It is my tribute to the city of the Golden Temple. In a way, I acknowledge the city and whatever it gave me, which formed who I would become later on. I think those 19 years had a lot to contribute to it.

When you talk of those 19 years, there is no bitterness. More so because you were born immediately after Partition.

We were not fed any bitter truths. Our parents didn’t talk to us about Partition and killings. We only heard about it here and there. Everybody knew of the massacres on both sides, but my parents did not talk much about that.

Was it a conscious decision?

Yes, I think so. There was my dad’s cousin sister who was abducted and killed at the Beas. They never talked about it. We would hear from outside of the Lahore massacre which started four months before the Amritsar massacre. For a time, I grew up thinking that Muslims were cruel people. Only when I became a girl, our tenant upstairs told me, ‘ Beta, dono taraf wahi hua hai, yahan bhi qatal-e-aam aur wahan bhi [child, this is what happened on both sides, there were mass killings here and there]’. Nobody spared each other, it was a bad time.

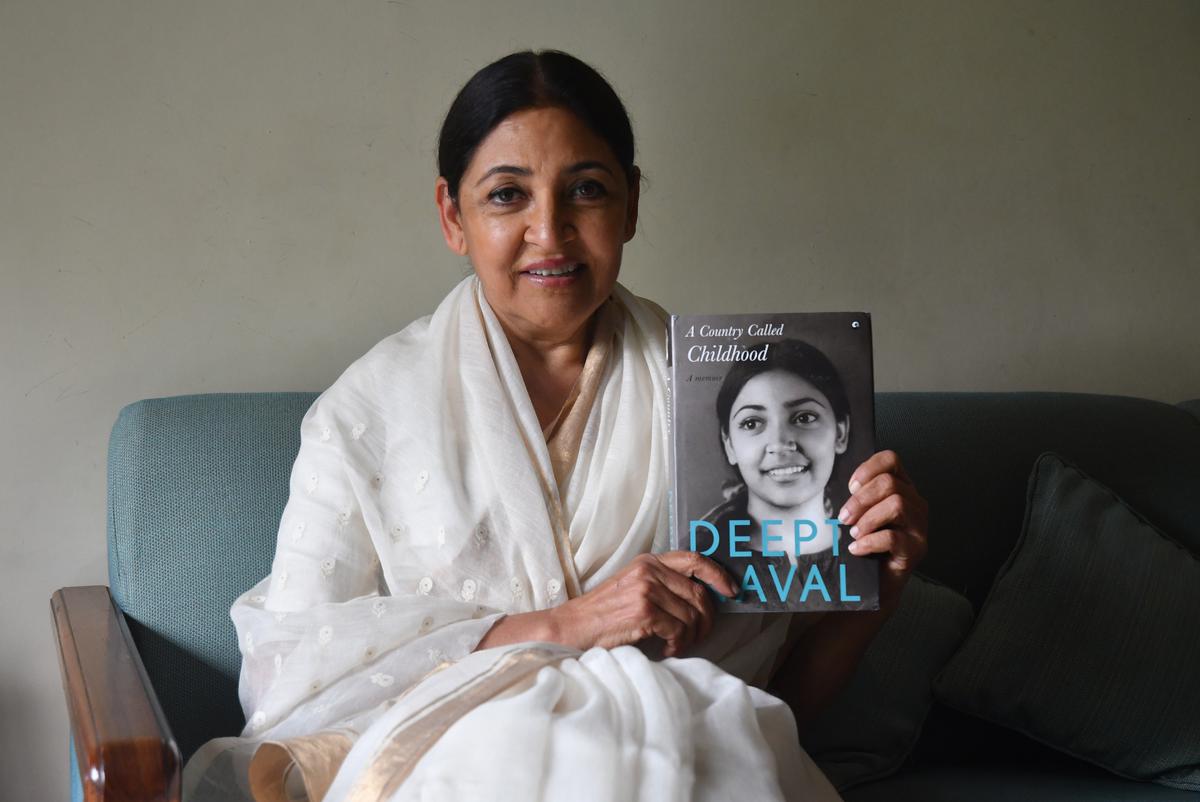

Deepti Naval with a copy of A Country Called Childhood, published by Aleph Book Company

| Photo Credit: Sushil Kumar Verma

Your father told a heart-warming tale of the masjid next to your house.

Yes, that happened four days before the Jallianwala Bagh incident [in 1919]. The British had killed about 25 people of different religions. The bodies of Hindus, Muslims and Sikh were taken to the maseet to perform their last rites. In retaliation to the deaths, a jalsa [function] was held. This is the story I heard when I was a child.

Wasn’t this tragic tale in a way an affirming story of shared living where your religion did not matter?

Yes, we considered the maseet a place of worship. We used to think, like Sikhs have their Guru Granth Sahib paths, the Muslims have their azaan and namaz. As kids, we thought the maseet adjacent to our house was ours too. We were listening to the azaan five times [a day]. It became part of our lives. There was acceptance of all strands of faith.

You talk of aiming to go to J.J. School of Arts in Mumbai, but your parents were not able to send you. A career in films was a no-no, too. And you mention a friend who was not allowed to perform Kathak in public. Was this denial of opportunity to the girl child a constant in society?

My father could not afford to send me to Bombay; we did not have the funds. I learnt Kathak, but I could never use the skill in Hindi cinema. As for girls being denied opportunities, my mother was inclined towards the arts, but could not pursue it even though my grandmother was progressive. My mother had been a refugee twice — first from Burma and then from Lahore. My grandfather took a ₹1 coin as dowry, as a token that we don’t believe in the dowry system or in idol worship. We are Arya Samajis; we believe in abstract god. No other rituals. But even after all this, the ‘ log kya kahenge [what will people say]’ aspect was still strong.

Actor-writer Deepti Naval

| Photo Credit: Sushil Kumar Verma

You mention in your book that ‘girls from good families don’t go to the cinema’. Yet, you went to so many…

As a little girl of four, I was found staring at half torn posters outside a cinema and my grandmother scolded me for it. [But] I have watched many movies while bunking classes with girls. We only visited Chitra Talkies, Adarsh Talkies, Nandan cinema, etc; we never went to the sleazy ones.

Did watching Meena Kumari and Sadhana on screen sow the seeds of cinema in you?

Yes, I felt this from the beginning. I used to love Meena Kumari, and then Sadhana. I loved her fringes. I had fringes, too. I felt that the work done by performers was so important. They were emotionally connecting with us. And I wanted to do that, [so] people would start identifying with me. They would think that I am speaking their mind.

Did your middle-class upbringing become an obstacle?

Yes, I assumed I would not get permission from my parents to join films. It was alright to be a classical dancer and perform on stage, but films were for the masses. Later, my whole family settled in the U.S. and I would have to come to India alone. I was from Amritsar, and there was no family support in Bombay.

Towards the end of the book, you talk of your family’s departure for the U.S., using the simile of pigeons at the mosque’s dome coming for a while, then flying away. Did your story seem like that?

Yes, it did. I used to see these pigeons at the dome of the mosque. They would fly away, but come back after a while. I also came back — not to Amritsar but to Bombay.

Was it fitting, then, that the first film narrated to you was the story of Ruskin Bond’s Flight of Pigeons?

Yes, absolutely. It became Shyam Benegal’s Junoon.